Long before they heard about the Texas bullet train, Mary Meier and her husband were accustomed to companies coming after slices of their land. A fifty-foot-wide oil pipeline easement bisects their 25-acre property in Montgomery County, north of Houston, where they’ve lived for sixteen years. But when she learned that a 200-mile-per-hour Japanese-designed train might speed by every thirty minutes, just two hundred yards from her kitchen window, carrying travelers between Dallas and Houston, she was furious. There was the practical concern: how would she access the half of her property on the other side of the tracks? The train’s builders had advertised that some sections of the rail would be elevated to allow passage underneath, but Meier doubted whether such access would be provided on her property. Then there was the matter of principle. “Your property is where you have peace and serenity,” she said, adding that the main beneficiaries of the train wouldn’t have to deal with its adverse consequences. “It’s all fine and good if you’re living in an apartment in downtown Houston.”

Ultimately, the proposed route moved off Meier’s land and the surveyors never came. But she still staunchly opposes high-speed rail on behalf of other landowners in the ten counties along the Interstate 45 corridor where the train would run.

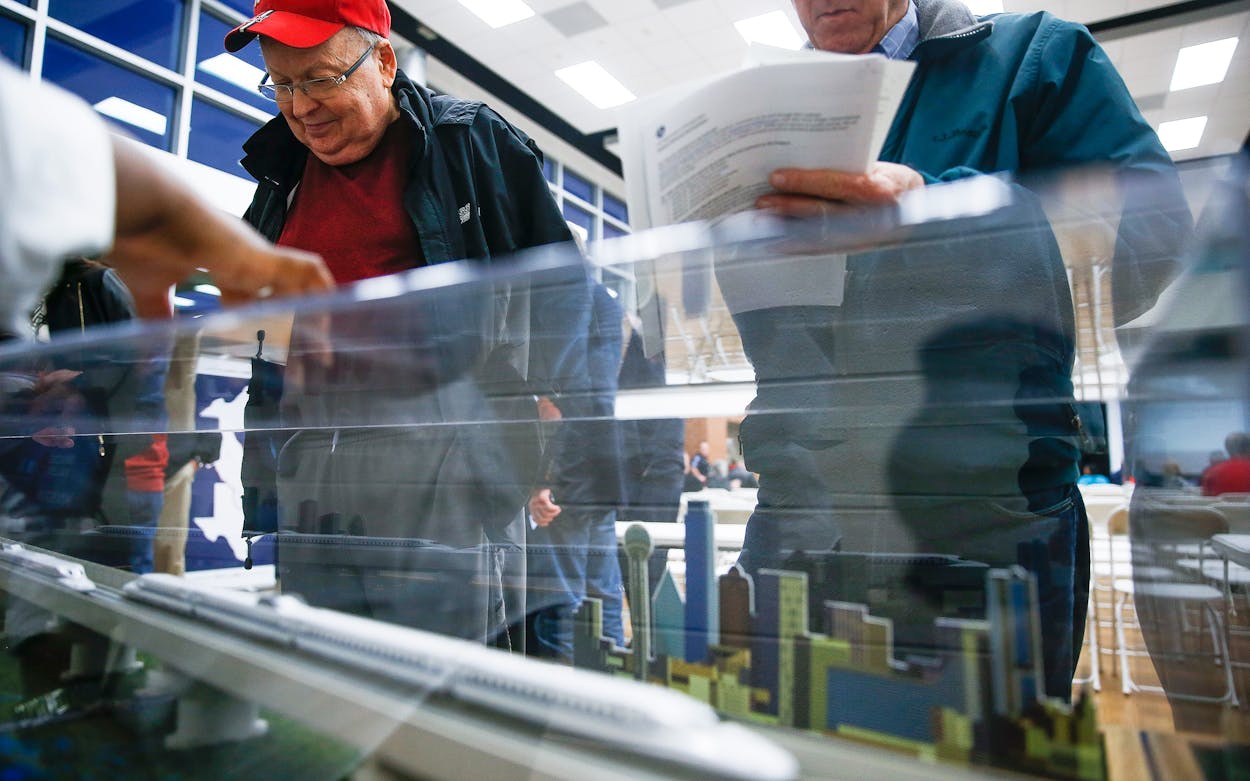

Earlier this year, after six years of legal battles brought by property owners and local governments, the rail project finally looked to be chugging along. Texas Central, the company behind it, had purchased six hundred parcels, or 40 percent of the land needed to build the project. In May, a victory at the Corpus Christi Court of Appeals asserted the business’s status as a railroad company with the power to exercise eminent domain—meaning that it can require owners to sell portions of their land in return for a “reasonable” price—though that ruling may be appealed to the state Supreme Court. This fall, the project received approval from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Railroad Administration, and Governor Greg Abbott wrote a letter to the Japanese government, a key investor in the project, voicing his support. The potential benefits of the rail seemed manifold. It would offer travelers a ninety-minute alternative to the four-hour drive between Dallas and Houston and relieve highway congestion that’s projected to double by 2035. It would reduce greenhouse gas emissions. And it would create thousands of high-paying jobs at a time when Texas is suffering from both a pandemic-related recession and an oil-price bust.

“The Texas High-Speed Train will be the first truly high-speed train in Texas and the United States, connecting North Texas, Houston and the Brazos Valley in less than 90 minutes, using the safest, most accessible, most efficient and environmentally friendly mass transportation system in the world today,” Texas Central spokesperson Erin Ragsdale wrote in a statement.

Abbott’s letter, however, sparked a firestorm among some of his longtime supporters. Even before the governor expressed support for the rail project, Meier said, her circle of friends had become increasingly wary of him because they believed he was pandering to liberal interests by imposing restrictions on some businesses during the early days of the pandemic. “I was the only one I know of that was still basically supporting him,” Meier said. “If he continues to support the [train], he will not get my vote, and I will passionately spread the word.”

Four days after Abbott penned his letter, his staff walked back his support, telling the Dallas Morning News that the governor intended to reevaluate his position out of concern for Texans’ property rights and because he was provided with “incomplete” information about the project. (His initial letter had indicated the railway had already obtained all the necessary permits to proceed, but, in fact, it still needs to receive approval from the Surface Transportation Board, a federal regulatory agency.) Abbott’s office did not make clear whether staff, pro-rail lobbyists, or another party had provided the information that allegedly misled him, nor did it respond to multiple requests for an interview about why he wrote the letter and later walked it back. Texas Central also declined multiple requests for interview about Abbott’s reversal. With the loss of the governor’s support, the train’s future faces new hurdles. Texas Central now lacks a strong advocate to ward against pending anti-high-speed rail bills in the upcoming Legislative session, and the company has lost a prominent voice asking investors to keep money flowing.

The project would benefit millions of Texans in Dallas and Houston and cities and towns in between, as well as many Texans who might never set foot on the train but who would be relieved of having to battle crippling congestion on I-45. But those potential beneficiaries are far less organized than are the train’s critics. For years, an army of county judges, landowners, lawyers, and right-wing interest groups such as Tim Dunn’s Empower Texans have opposed the project under the banner of property rights. Railroad companies, however, aren’t the only ones permitted by Texas law to acquire land through eminent domain. Oil and gas pipeline companies typically acquire rights to far more private land every year than what’s being sought by Texas Central. (The holding company that owns Texas Monthly also owns interest in oil and gas pipelines, among other diverse investments.) Also, according to Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts data obtained by the Texas Pipeline Association, 82 percent of eminent domain condemnations in 2013 were conducted by government agencies, prominently including TxDOT. Both pipeline and highway projects draw protests, especially when they would affect the ranches and weekend homes of large numbers of influential Texans in areas such as the Hill Country. But those objections pale in comparison with the outrage and lobbying aimed at the bullet train.

Luke Ellis, an Austin-based lawyer, represents clients in lawsuits against Texas Central and also against Kinder Morgan for its Permian Highway Pipeline Project that would connect West Texas oil fields with Gulf Coast refineries. He says that when oil and gas pipeline companies use eminent domain to acquire land for pipelines, landowners know what to expect. Using data from sales of other tracts, they can anticipate what they’ll be paid for an easement and the impact on their property value. But, with high-speed rail, rural Texans feel they are going in blind. Meier, for one, said she worried her property value would be tanked by noise, vibrations from the train, maintenance crews coming on and off her land, an easement much larger and more intrusive than those used for pipelines, and other unknown variables that could arise from the unusual project.

Some critics also appear to be motivated by xenophobia. Texas Central is a Dallas-based company, and Texans would be the largest beneficiaries of the rail. But investment from the Japanese government is crucial to the project. In an April letter written to Senator Robert Nichols (R-Jacksonville), Drayton McLane Jr., the chair of Texas Central Partners, emphasized the project’s dependence on Japanese government funding. He stated that the rail line that originally was estimated to cost $10 billion now is expected to cost three times as much. In Abbott’s initial letter offering support to the train, he too wrote that Japanese cooperation was necessary for construction to begin. Ellis told me that “a lot of folks have a gut opposition to that.” He said the project’s opponents remain adamant about a particular interpretation of the Fifth Amendment’s final clause: “nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.” “There are those who think that because this project is being funded by foreign nationals, that doesn’t constitute the American public,” Ellis said.

Texas Central has responded to such critics. “Despite unfounded rumors to the contrary,” CEO and president Carlos Aguilar wrote in a September statement, “Texas Central Railroad, a Texas-based company, owns the property purchased for the state-of-the-art high-speed train project.”

While Abbott’s backtracking might have been influenced by one of his constituencies’ disdain for the project, the financial uncertainty also surely had a large effect. Texas Central has maintained that the high-speed rail project is a private venture financed “with a blend of debt and equity.” But some, including Kyle Workman, president of Texans Against High-Speed Rail, an organization run by rural anti-rail politicians and attorneys, worry that the project will be deemed “too big to fail” and later require high levels of federal subsidy at the cost of taxpayers.

Indeed, a week after Abbott’s original letter to the Japanese prime minister, a group of seventeen Republican Texas legislators sent a letter to the governor expressing fears that public funding would be used for the bullet train. “Texas Central’s last hope is an infusion of money from Japan and the enactment of the Green New Deal, providing a taxpayer bailout on the project before it ever even gets started,” the legislators’ letter read. “[The bullet train is] a project destined to leave the taxpayers on the hook for this financial boondoggle.”

The same group of Republican legislators met with Abbott right before Thanksgiving to make their case against the train. According to one of the representatives in attendance, Ben Leman of Anderson, Abbott is still making up his mind. Until he does, the project’s fate may be determined by the Lege. In early November, Steve Toth, a GOP representative from the Woodlands, pre-filed House Bill 114, which aims to restrict the ability of state agencies to grant high-speed rail permits. More anti-rail legislation from Republican legislators is expected. In the absence of outspoken advocates, the session may kill any momentum the project had left.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Greg Abbott