Several years ago, New York magazine ran a wonderful feature called “One Block,” interviewing the inhabitants of a block of rowhouses in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. Speaking about the area’s troubled past—it was ground zero for Robert F. Kennedy’s campaign against urban poverty, and, later, unfairly a byword for a dangerous inner-city neighborhood—one older Black resident made the distinction between “block people” and “avenue people.” Block people tended to be homeowners and their tenants, middle-class and stable. Avenue people were low-income renters in poorly maintained housing. They came and went, and the implication was that they were responsible for most of the neighborhood’s problems.

I’ve thought about that dichotomy a lot since, because it’s a neat way of summing up the way that zoning, architecture, and social class interact. It not an accident that American neighborhoods tend to have apartment buildings on their busy thoroughfares and one- or two-family homes on the side streets. Ironically, Bed-Stuy is a bit of an exception in this regard, since much of the neighborhood was built before the zoning that formalized what kind of structures would go where: In Brooklyn, there are apartments on side streets and rowhouses on big avenues.

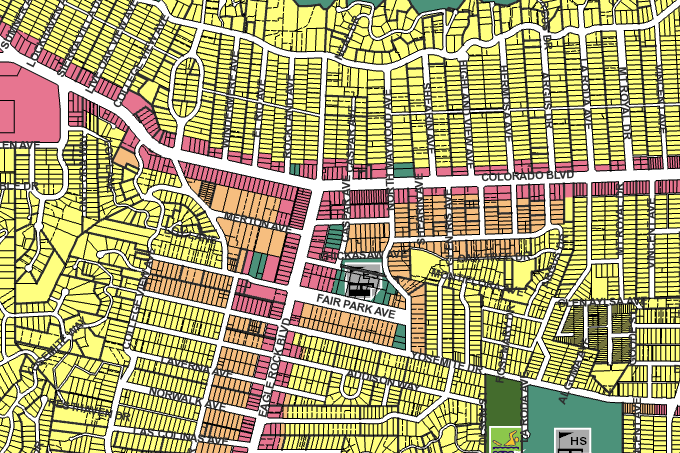

The distinction between Block People and Avenue People is alive and well, however, in most American neighborhoods, where it’s a planner’s article of faith to encourage dense development along major corridors and nowhere else. Unfortunately, big streets are not nice places to live. Their traffic is noisy, dirty, and dangerous. Allowing apartment buildings to be built at all is progress, but ensuring they rise only in the worst locations is not fair to the people who live in them.

As Daniel Oleksiuk wrote recently in Sightline of this practice in Vancouver, British Columbia, “Instead of planning for housing options in locations that maximize the health and well-being of residents, policymakers are mandating that people who prefer more compact, energy-efficient, and lower-cost homes can only live on traffic-choked arterial streets—and must suffer all the bad health consequences.”

This is also the conventional wisdom in American cities like Los Angeles, Seattle, and Washington D.C., where for a few different reasons, everyone has decided that the biggest commercial corridors are where the apartments go.

First, it’s a way to permit new housing without disturbing the single-family life of the neighborhood. That makes it easier to get approval for new buildings. But that doesn’t mean it’s a good idea. In Vancouver, as Oleksiuk points out, larger buildings on busy streets are explicitly intended to “shield, to some extent, adjacent single family homes from the noise of arterial traffic, …act[ing] as a buffer.” Nobody deserves to be a living buffer.

Second, this practice relates the height of buildings to the width of streets. Putting bigger buildings on bigger streets lets more light reach apartments, storefronts and sidewalks. And yet there’s actually more space between two houses on a typical suburban block in Los Angeles (about 100 feet) than between buildings on Broadway in Manhattan (about 70 feet). This ratio is only loosely followed, in other words, and the benefits of sunlight do not outweigh the harms of air pollution.

Third, big urban streets tend to be transit corridors, and it makes sense to put more housing near transit. That’s true. But that logic should apply to neighboring streets as well. A side-street that’s a short walk from transit is also an excellent candidate for a high-rise.

You don’t have to go to Madrid to see what it feels like in practice to have mid-rise buildings along a quiet residential street. Try this block of North Paulina Street in Chicago:

The downside of demanding this type of housing go only on bigger, busier streets isn’t just the opportunity cost of many foregone apartments on smaller streets. It’s also that living on a busy street is terrible. You get dust on your countertops and bookshelves. Passing trucks and subwoofers and Indian choppers rattle your glasses. The headlights and sirens at night and the noise of constant traffic, which may be linked with dementia, when you open your windows. The pollution associated with busy roads, in particular, seems to be linked to a new health problem every day, especially for children.

On top of it all, once you leave your home, you are on the type of street on which you’re most likely to be killed by a car. You’re not likely to let your kid play in front of the building, let alone walk to a friend’s place.

The final reason for this injustice is, ironically, the very traffic that makes our apartment corridors so hazardous. It’s assumed that new buildings will contribute to traffic, and so they must be built on streets that can accommodate more traffic. And you wonder why no one wants to ride a bike down, say, Washington, D.C.’s Connecticut Avenue NW.

Many critics have rightly pointed out, in recent years, that zoning in residential neighborhoods seems a lot more concerned with types of neighbors than with the supposedly hazardous consequences of their arrival. This may be true of the complaints of community members. But for professionals, as UCLA’s Donald Shoup has noted, “cars have replaced people as zoning’s real density concern.” This is why city planners endorse the idea that a four-story apartment building must be on a six-lane arterial road instead of two blocks over. They often require these new buildings include parking, of course. And if the buildings don’t have parking—a relatively novel innovation in many places—cities have gone so far as to force developers to require tenants not to own cars in their rental contracts.

The block people, in other words, cannot have the avenue people contributing to traffic. Breathing in its exhaust is another story.