Manhattan’s avenues stretch north like tracks through a forest, eventually disappearing into Harlem. Below me, Central Park is laid out like a picnic blanket, its largest trees rendered shrub-like. To the south, the Empire State Building pierces the city’s canopy of stone and iron, and the blue glass of the new World Trade Center glints beyond it. Between them, the Statue of Liberty is almost lost in the haze.

This is the view from the world’s highest home, as enjoyed virtually, using Google Earth. Because to enjoy it in person would require knowing the unnamed owner of the 800 sq m penthouse at 432 Park Avenue – or buying it for more than the $88m (£71m) it sold for last year.

But there are alternatives for those with a head for heights and the money to match. Next year, the 426m Park Avenue tower will lose its title to 111 West 57th Street, rising two blocks to the west. Meanwhile in India, the 442m Mumbai World One will push higher still, its Armani-designed penthouses on level 117 offering airliner views of the Arabian Sea.

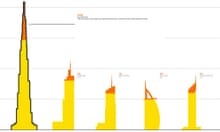

Once, only offices reached so high. In 2000, there were 215 office towers worldwide above 200m high (the first, the Metropolitan Life Tower in New York, was completed in 1909), but only three residential towers that high. Today, there are 255 residential towers above that height, with a further 184 under construction. Mixed-use towers, with apartments as well as offices and hotels, include the Burj Khalifa, still the world’s tallest building, at 828m. The Jeddah Tower in Saudi Arabia, due to be completed in 2020, will be the first to break 1,000m. Its highest apartments will be on the 156th floor.

What is life like up there? For decades, tower blocks typically comprised social or affordable housing in crowded cities or on new estates. Hundreds were built in the postwar social housing boom, in cities across Europe. But today the highest residential towers are overwhelmingly luxury developments, and many remain empty, weeks after selling. If skyscrapers broke ground as barometers of corporate hubris, increasingly they now stand for personal excess, applying gravity to the wealth divide.

Britain, traditionally a low-rise country, is part of the boom. Skyscraper clusters are casting shadows across London. In Manchester, the first 200m building outside the capital is due for completion next year. Even in Bristol, where St Mary Redcliffe church has been unrivalled in its heavenwards reach for more than six centuries, there are plans for a 22-storey residential tower that would come close.

Jason Gabel, an urban planner at the Chicago-based Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, which keeps a global skyscraper database, says advances in building technology partly explain the trend. Lifts can now travel at more than 40mph and climb for hundreds of metres, thanks to lightweight carbon fibre ropes. Sophisticated dampening systems at the tops of towers mean slender buildings can rise higher, on smaller urban plots, without toppling in a storm or swaying to the point of causing nausea.

For a growing number of city dwellers, day-to-day life can be a little different. The payoff for peace and endless views can be five-minute waits for the lift at rush hour – and even sunburn. “You could get tanned in winter if you sat right by the window: there’s a bit of a greenhouse effect,” the owner of a 64th-floor apartment above Chicago tells me. Vertigo can be another danger. At the top of a tower in east London, former taxi driver Sammy Dias rarely uses his balcony: “I don’t like heights, and if people go out and start messing about, I can get quite angry,” he says from a safe distance inside.

I spoke to residents around the world, and many reported feeling uplifted by their elevated perspective, but there are hidden downsides: a Canadian study of heart attack victims showed survival rates dropped markedly on higher floors, because they were harder for paramedics to reach.

Skyscraping homes have always held an allure; a house with a view, a life in the sky. They frequently evoke dystopian imagery; Ernö Goldfinger’s troubled Trellick Tower in west London, completed in 1972, is thought to have inspired JG Ballard’s dark thriller High-Rise. It was originally entirely owned by the Greater London Council, and rented out as council flats. Now social tenants of the Grade II*-listed building, and its sister, Balfron Tower in east London, are being displaced by upwards gentrification. Less desirable council towers are reaching the end of their habitable lives, facing decay, demolition or expensive repair.

Meanwhile, the upper floors of many new luxury skyscrapers serve as foreign cash stores: giant briefcases with views. The highest homes in Britain are the 10 luxury apartments between floors 53 and 65 of the Shard. They are among the most opulent in London, yet almost five years after their completion, none is occupied or even for sale or rent. The reason remains a mystery.

“Stacking people on shelves is a very efficient method of human isolation,” says Jan Gehl, a veteran Danish architect and renowned urban design consultant. A critic of residential towers even where they are fully occupied, Gehl likens them to gated mansions in the sky. Humans, he says, did not evolve to look up or down: “We have seen, in the past 20 years, a withdrawal from society into the private sphere, and towers are an easy way to achieve that.”

Is this the experience of those who live above our rising cities? Finding out isn’t easy; even when – or if – they are home, residents of the most rarefied apartments in the world are hard to identify, much less reach. But all human life is there, way up on the 64th floor.

Mike Palumbo, 50, trader; Water Tower Place, Chicago

Chicago born and raised, Mike Palumbo is a Bulls fan who grew up on the edge of the city, the son of a truck parts salesman. From a corner near his house, he would gaze at the John Hancock tower, the matt-black, tapering monolith near the lakeshore, and dream big. “When I hit 13, I went to high school downtown,” Palumbo says. “I would take the L train to within a block of the John Hancock. Back then, there was this guy called Spiderman who’d climb up it with suction cups. I loved it. I’d walk around and I was like, man, I’d rather be in the city where all the action is. This is me.”

Palumbo became a fund manager and in 2007 made $100m. For 18 years, he has lived in an eight-bedroom apartment on the 64th floor of Water Tower Place, an exclusive residence right across the street from his favourite skyscraper. Oprah Winfrey used to live a few floors down, Palumbo says as we look out, and down, on a forest of skyscrapers. David Axelrod, President Obama’s chief strategist, remains a neighbour and chairs the pets committee on the building’s management board. “I’m a dog lover, but there are people who don’t want them in the building,” says Palumbo, who also sits on the board. “You try to get along, but you’ve got a lot of very successful people arguing over minuscule things.”

Half of Palumbo’s apartment is a man cave, with cigars in a jar on a bar next to a pool table. The other half is crammed with the accessories of parenthood: Palumbo and his second wife, Veronica, had twins last year, and their nanny lives with them. They add five minutes to any journey to allow time to get everything into the elevator. He has four grown-up children from his first marriage, who often visit.

As a young trader, Palumbo got job offers from Wall Street, but never wanted to leave Chicago. “I just love this view,” he says. “When I wake up in the morning, the first thing I do is open the blinds and let the sun come in. It doesn’t get any better.” Yet he is also scared of heights. “I’m OK with the windows, but if this was a ledge, I’d be freaking out right now.” He opens the window and a gust of wind slaps our faces. A spider’s web somehow still clings to the frame. “I never understand how these guys get all the way up here,” he says.

Below us, I count more than a dozen rooftop swimming pools. The 423m Trump Tower dominates the skyline to the south. Later, a cleaning cradle winds past and the men with rags avoid looking through the glass. “I would not want that job,” Palumbo says.

Ian Simpson, 61, architect; Beetham Tower, Manchester

Ian Simpson is from a family of demolition experts and grew up in a poor northern suburb of Manchester. “I spent my youth climbing up mill chimneys and blowing them up,” he says. “But, somewhere along the way, I went from knocking things down to putting them back up again.”

Simpson became one of Britain’s leading architects and has been instrumental in Manchester’s regeneration, not least since an IRA bomb destroyed large parts of the city centre in 1996. He now occupies a unique position at the top of his own skyscraper, a steel-and-glass eyrie from which he surveys a city he has helped shape. At 47 floors, Beetham Tower cuts a lonely, slender figure above south Manchester, the tallest building in Britain outside London. “Nobody thought it was going to stand alone,” Simpson says in his vast, two-storey penthouse, which includes what may be Manchester’s only olive grove. “Other tall buildings had consent, but then we hit the recession.”

For 10 years, Simpson and his partner have enjoyed uninterrupted views. “The light here is spectacular,” he says. “It animates the space as it moves around; I find it very uplifting. It’s like a little oasis right in the city.” But the architect is happy that Manchester is on the rise again. There are plans for almost a dozen new towers above 30 storeys, chief among them the Owen Street development. Designed by Simpson’s practice, which he leads with architect Rachel Haugh, it will include a 200m tower of 49 floors, a new high for the city.

“This is what Manchester needs,” Simpson says. “Historically, nobody lived in the city centre. If you had money, you lived in the leafy suburbs to the south; if you didn’t, you lived to the north like me. That’s changing, and we need to have a critical mass to create the jobs and demand for everything else, whether it’s bars and restaurants or infrastructure.

“I have a lovely painting in my office down there of the city in the 18th century. It was a city of towers – but they were mill chimneys. When that changed, there were gaps, which generally became car parks. We want to fill those gaps and intensify the city, not spread it out.” Like those chimneys, Simpson says, “tall buildings provide not only a function, but also an image of confidence”.

We move from the living area into the olive grove, which occupies a sort of penthouse conservatory, facing south. Thirty miles to the west, Liverpool is visible on a clear day. The trees, more than 30 of them, were shipped from Italy and lowered through the roof before the building’s crane came down. “They love it up here,” Simpson says. “But there’s no pollination: we don’t get any bees this high, so there are no olives.”

Farimah Moeini, 35, media sales manager; Ocean Heights, Dubai

As a teenager in Tehran, Farimah Moeini would often fly to Dubai with family and friends. She knew only the old town because that was all there was. “Everything you can see here was sand,” she says via video call from the Dubai apartment she shares with her British husband, Luke, and their baby, Liam. “The Palm, Dubai Marina, all these towers: none of it existed. I remember going to the older malls. We’d have shawarmas and try to get into bars and clubs. Then it started to grow – and it hasn’t stopped.”

Moeini left Tehran, where her father owned a textiles factory, to go to college in the US. In 2009, she got a job with Yahoo and moved to Dubai at a time when rents were cheap following the global financial downturn. She met Luke, who works in real estate, the following year. They live in a one-bed apartment on the 68th floor of Ocean Heights, a residential block in the marina. Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building, looms 13 miles along the coast.

“You do feel as if you’re in a bubble,” Moeini says. “Sometimes I pinch myself, because a lot of the lifestyle is not really real. It’s all so clean and neat and safe. There’s a cultural bubble, too. When I was 16, you would hear Arabic music and see local people everywhere; it was more authentic. I also miss nature. In Iran, we have four seasons, and it’s beautiful when they change. Here, years go by and you don’t know where you are.

“But it’s a nice bubble. It’s fun and easy to meet people from all around the world. It’s a happy place. I also love being up here – it’s insane how calm you feel. Just waking up every sunrise and staring out to sea is so soothing. If I sit on my sofa and look out, I can only see sea and sky. And they are real.”

Sammy Dias, 77, retired taxi driver; Petticoat Tower, London

For more than 30 years, Sammy Dias has lived in Petticoat Tower, a 1970s council block owned by the City of London Corporation, and for most of them he’s been on the 21st floor, two down from the roof. On a sunny January afternoon, he draws back the net curtain in his living room and looks east towards Stratford.

“Look at that – you see the Olympic Stadium there?” he asks. The building’s zigzag roof supports come into view three miles away. Since the 2012 Games, it has become dwarfed by taller apartment buildings. “Just look at the amount of flats that have gone up: it’s unbelievable. It’s almost happened overnight.”

Dias drove a black cab in and around the Square Mile for 45 years, until he retired five years ago. From street level and above, he has watched London rise. The Gherkin, just 200m away, casts a shadow over his building. 110 Bishopsgate, with its rooftop sushi restaurant and exposed lifts, rears up just two streets to the west.

Dias turns his gaze down over Aldgate, a hodgepodge of housing and mushrooming hotels, and Petticoat Lane market, where clothing has been sold for centuries. “I worked down there when I was an 11-year-old, pulling barrows out,” he says. “Every stall sells the same thing now. You see that brown building there? That’s where I was born: number one Herbert House.”

Dias didn’t plan to live high up, and never uses his tiny balcony. He hates heights. “I’m OK sitting here, but I can’t go out there. They call this the haunted flat – there’s been a suicide from that balcony.”

His first flat here was on the 11th floor, but he and his wife, Phyllis, a jeweller’s bookkeeper, moved up in 1994, when a two-bed flat became available. Soon after, she developed Alzheimer’s disease; she died in 2001.

“It took a while to get used to living here alone, but I have a good routine now,” Dias says, sitting in one of the room’s two armchairs. Photos of the couple stand on an old dresser. “Sometimes I wake up early and lie there and reminisce, or I might read the paper. Then I get up, have a wash and the radio goes on. I listen to Radio X with Chris Moyles. I can’t stand him, but I love the music. Later, I’ll go out and meet the little old boy on the estate with the frame. We go to the Bell, where I had my first drink aged 16. I’ll have two pints of lager, then two – maximum three – gin and lemonades, come back up here, have my grub, get relaxed and go to bed.”

Dias plans to live out the rest of his days here. “My mind is all there. I went to school up until age 11, and I could still tell you everyone who was in my class. It’s the genes; I’ve got a 90-year-old sister and we have a conversation on the phone. April the first I was born, I was married April 1st and, the way I feel sometimes, I’m gonna snuff it on April 1st. I’ll do the treble.”

A City of London housing officer recently came to discuss a move into a one-bed flat. Dias had suggested it himself, but declined when it became clear that it would mean leaving the building. “I said, I’ve got friends here! This is my area. I’ve got everything and I’m happy. Do you know what I call it? I call it my castle.”

Traci Ann Wolfe, 40, actor; 8 Spruce Street, New York

“It’s weird to live in a building where all these tourists are pointing their cameras up at you,” says Traci Ann Wolfe, looking out over lower Manhattan from the 50th floor of 8 Spruce Street. Designed by Frank Gehry, the 76-storey skyscraper’s facade appears to ripple like wind across water. Yet such delicacy belies the brute financial imperative that made it the tallest residential tower in New York, and indeed the western hemisphere, when it was completed in 2011. “Forget about Gehry, it’s the view that makes me so grateful,” Wolfe says. From her corner flat, she has a near 180-degree view of the tip of Manhattan: the Hudson river to the west, One World Trade Center straight ahead, then out to the East river. The panorama is as exhilarating as a helicopter ride. “We’ve seen bolts of lightning touch the tip of the Trade Center.”

Wolfe, an actor and former model, moved to this one-bed apartment four years ago with her husband, a hedge fund manager. The rent is pricey for what she confesses “feels like a kitchen with a bedroom” (its official 900 sq ft size feels a shade optimistic), but she and her husband are very happy here.

Living this high up, though, can be eerie, and the wind intimidating: “The building creaks like an old boat, and you can even feel it sway.” Security pins had to be added to the windows after it was discovered that high winds could prise them open: in one early incident, a TV was sucked out of an upper-floor apartment.

A few months after we first speak, Wolfe and her husband move out of the building they called home for five years. They now own a house in Southampton, New York, and rent an apartment in an eight-storey building in Manhattan, swapping the 50th floor for the sixth. “It’s more of a nuts-and-bolts experience,” Wolfe says. “I hear the cars, people in the bar across the street, construction noise, helicopters. It’s wonderful to feel the energy of the city, which can be a huge motivation, but it can also be a distraction. On the 50th floor, I was more removed from it all. It’s comforting to sense the ground beneath me – but I would prefer to dream above the clouds.” Interview by Justin McGuirk

Tyrese Mhlakaza, 24, nightclub promoter; Ponte City, Johannesburg

When he was 17, Tyrese Mhlakaza left the small town near Durban where his single mother had raised him and his siblings, and moved to Johannesburg to start his adult life. “It is the city of dreams,” he says. “I moved here to find work and to survive as a man. It was the first time I had been, and the weirdest thing at first was that there was no beach.”

Johannesburg, a city of almost 5 million people, built on the site of a 19th-century gold rush, is home to Africa’s tallest residential building. Ponte City, a 55-storey concrete cylinder with an open core, was built in 1975, and became the booming city’s most desirable address among its wealthy minority white population. The three-storey penthouses had saunas and hot tubs.

But economic strife and suburbanisation in the 80s sent the tower into a spiral of decay and crime. Gangs moved into what became an urban slum. Rubbish filled the central core. Post-apartheid uncertainty furthered the building’s neglect, but by the turn of the century it had begun to symbolise the city’s revival. After a total refurbishment, it is now desirable again, and affordable, too.

“I’d say it’s 80% black now,” Mhlakaza says from level 53, where the penthouses have been split into flats. He lives with his brother and three friends, paying about 9,000 rand (£540) a month in rent between them. “We have people from Mozambique, Zambia, Nigeria, Ghana, Zimbabwe, and a lot of the white people are from Israel and Australia. South Africa is all about the rainbow nation and it doesn’t get any more rainbow than this.

“I love living up here,” he adds. “I can see almost all of my city and I’m obsessed with views. I love looking out, and I always loved being outside where I grew up. The fact that I can see so much makes me feel as if I’m outside.”

Mhlakaza, who was born two years before the end of apartheid, got work as a waiter and a barman. He now does public relations for a nightclub not far from the tower. He can see rugby being played below him in Ellis Park Stadium, where Nelson Mandela watched South Africa win the World Cup in 1995. His home town lies 300 miles farther south. He has no plans to return, and wants to become a lawyer.

“I go back in the holidays, but I don’t see home the same way I used to,” he says. “Living here changes your perspective. In a small town, people are not out-of-the-box thinkers. If you tell them your ambition, they say, ‘Oh my God, you wish.’ In Johannesburg, they say, ‘OK, what’s your plan?’”

Roz Kaldor-Aroni, 54, CEO of a medical research charity; Eureka Tower, Melbourne

When she prepares to drive her teenage son Gideon to school each day, Roz Kaldor-Aroni doesn’t bother with traffic reports. “I just look out the window,” she says by phone from Melbourne, where she lives on the 74th floor of the Eureka Tower. She and her husband moved to the 91-storey skyscraper when it opened in 2006. It was then the world’s tallest residential building; it’s now the 14th highest. “I have two ways we can go, and I can see the traffic from here and take the better one.”

There’s no need to check the weather, either, although low clouds can obscure the ground. “When they roll in, you lose all sense of distance and perspective. It feels as if you can reach out and touch the other towers coming up through the fog.”

The family, whose ears pop when they go home, are fine with heights, but visitors are not always so keen. “We had one babysitter who was so stressed out, she couldn’t come back.”

Australian cities, and Melbourne in particular, are experiencing a skyscraper boom. The city has set new limits on developments, but there are exemptions for sustainable projects. Eureka Tower will soon be overtaken by Australia 108, a 319m residential skyscraper. “We will lose part of our view, but we can’t really complain,” Kaldor-Aroni says.

The family enjoy the peace, but nature can feel remote. “When Gideon was little, he came back from a friend’s birthday party and said, ‘Mummy, we played in the park’, and I said, ‘No, that was their garden.’ I took him to the botanical gardens and made him smell the roses. But he looked at me as if I was talking a different language.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join the discussion, and explore our archive here