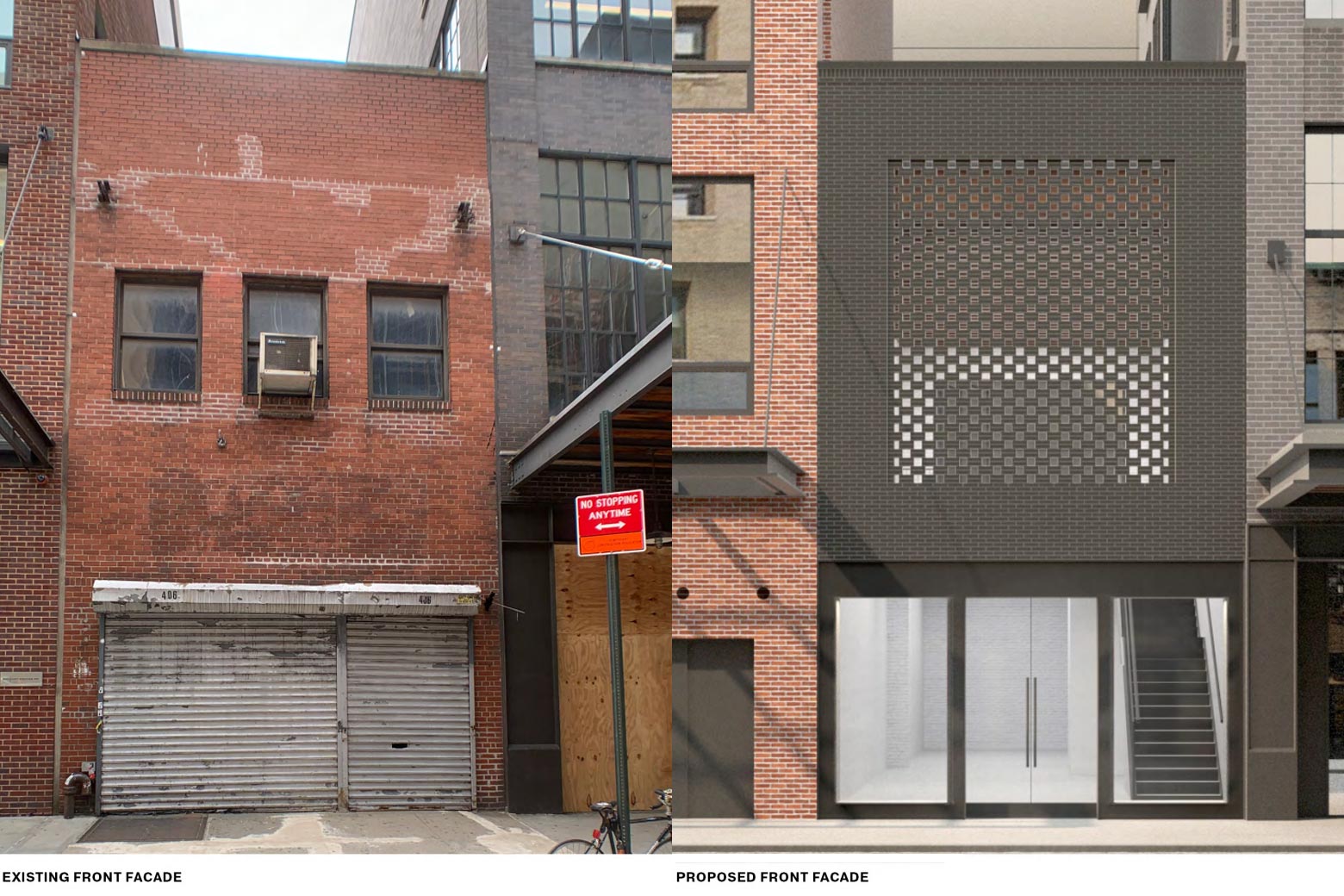

The building was two stories, brick without detail, three small windows over a metal roll-up garage gate—an eyesore if there ever was one, crammed between two taller neighbors. The proposed replacement was in gray brick, the creaky gate swapped for a glass-and-metal storefront, the windows making way for a delicate brick screen, to let the light in. Let your own eyes judge:

This is what the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission thought: The old brick building, said commissioner and architect Michael Goldblum, “is very much reflective of the period of significance of the district.” And the new building’s design, “while appropriate in scope, needs to be examined and made more location-specific … that’s not a very tangible direction, but I think it’s something the applicants can think about.” Sorry: The architects would have to try again.

Everyone knows there’s no arguing about taste. What the past half-century of urban growth in the United States presupposes is: What if there is? The promotion of good design in new buildings—distinct from the idea of preserving old ones—has become as much a local government objective as making sure every kid has a seat in school. Older American cities and suburbs are blanketed with zoning codes, historic districts, and design commissions that make sure communities that look nice stay looking nice.

A new wave of housing activists argues that this focus is a farce. In reality, they say, the ostensible interest in cornices, mullions, materials, rooflines, massing, and setbacks on new buildings serves as a convenient excuse for neighborhoods to keep everything the same—except for the socioeconomic diversity that once filled their sidewalks. Buildings that do survive the pageant arrive in a diminished state, bearing high rents that testify to their long delay and small stature.

“Time is money,” says Diana Lind, the author of Brave New Home, which argues against the single-family-home paradigm that keeps density out of expensive neighborhoods. “It’s the basic issue for most developers: Housing cost is only partly labor and materials. A lot of it is time and risk. Developers will talk about having an entire year to start building and factoring that into their cost.” In other words: Housing is more expensive, and less abundant, in the name of good looks. Not everywhere, but often in the high-opportunity neighborhoods and cities where it would mean the most.

It is hard to pinpoint what America’s era of highly supervised construction has achieved. This status quo has preserved the shape of older places, but not the kinds of people who once lived there. Instead we’ve manifested a landscape of historicist McMansions, parking podium towers, isolated commercial buildings dressed up in ornament like children on Halloween, landmarked gas stations and shoe-repair shops, and mishmash structures drafted by committee. This hyperlocal futzing is part of the reason that, in the decade following the Great Recession, we built the fewest new homes per capita of any period since World War II.

Tom Radulovich, the director of the San Francisco–based urbanist nonprofit Livable City, maintains that his town, which has the highest rents in the nation, ought to be able to have abundant housing that is also beautiful. But something isn’t working: “Something happened in the culture of architecture and design, which went from a system that was unregulated but consistently producing things that are good to one that is heavily regulated but still turns out crappy buildings,” he told me. But looking at places where architects have free rein, he added, “I don’t know that laissez-faire would get you better results.”

Many architects counter that it is the rules themselves—setbacks, lot coverage, drainage, parking, building height, one-family-only, Tudor houses here, Craftsman houses there, paint-it-like-so—that have put us in this position. Terrible buildings, and such small portions!

What’s to be done? Several recent confrontations have drawn scrutiny to the aesthetic regime. In D.C.’s Georgetown, a biochemistry professor commissioned two Transformers statues to stand outside his home, because they “represent human and machine living in harmony.” In New York City, a developer has proposed a tower of homes, some affordable, on a Lower Manhattan parking lot. In Connecticut, an apartment building of 94 units, some affordable, would abut the scenic Merritt Parkway. In each case, neighbors are upset. The Connecticut building is pending; the skyscraper has been sent back to the drawing board. The Transformers endure, tenuously, but you can’t live in a Transformer.

YIMBY activists—for “Yes in my backyard”—say the aesthetes have had their day, guarding the “cultural stability” of their fiefdoms only in the most superficial sense as mansions devour multifamily buildings and low-income people are exiled to the urban periphery. In Order Without Design, his book about cities and markets, the urban planner Alain Bertaud writes that the decision to build tall or short buildings is not the choice of an architect, developer, or planner, but a natural result of the land values, “purely an economic decision depending on the price of land in relation to the price of construction.” Requiring shorter buildings, as many places do, is tantamount to requiring expensive homes. (Some say that’s the point.)

The good news is that voters and politicians are increasingly coming around to the idea that single-family residential zoning is a tool of racial and socioeconomic exclusion, a relic that must be dismantled in the name of fairer, taller, and more compact cities.

The bad news is that a more difficult question looms: What to do about the way buildings look? Since the preservation coalition was born from the wreckage of urban renewal during the mid–20th century, the focus has shifted from protecting the old to policing the new. “It’s a movement from a kind of politics that presumes change is an inevitable and necessary part of urban life, with exceptions on occasion, to a model of urban politics that presumes change is harmful and unnecessary, and any change must be litigated, or else the city will cease to exist in the state it was in before,” observes Jacob Anbinder, a historian writing his Ph.D. dissertation on the postwar politics of urban growth. The result, he says, is a conservative feedback loop: “The less change occurs, the more people blame whatever problems they have on the few changes they see.”

The exclusionary version of design policing is common enough. In Connecticut, for example, the nonprofit Open Communities is pressuring the New Haven suburb of Woodbridge to rezone to permit multifamily structures no larger than the town’s existing single-family homes—not even to build bigger, just to let more people live there. In response, the town planner has proposed criteria that would govern the design of the new structures, though no such aesthetic ordinance existed before.

Then again, many urbanites hold a genuine belief they can make their cities look and function better without stopping progress. In the Philadelphia Inquirer, architecture critic Inga Saffron argues it is natural to care about the appearance of your surroundings: “It’s not unusual to hear YIMBYs declare that neighborhood character is irrelevant. They insist that any new apartment building is a blow for justice, no matter how grotesque its design. They seem incapable of understanding that it’s deeply human to care about what our surroundings look like. Context and details matter.” Pro-housing activists make a mistake, Saffron says, when they invariably identify their opponents’ interest in good neighborhood design as bad faith or bigotry.

In all likelihood, voters, politicians, and courts are going to cling to the idea that aesthetics are fair grounds to contest what happens on a neighbor’s property. But in a time of extreme housing scarcity and out-of-control rents, is a great-looking building still a luxury we have time to wait for?

The most difficult places to build in America are historic districts and their less distinguished cousins, “conservation districts.” In these neighborhoods, designs must pass muster with a board of volunteers, paid appointees, or city staff. In many cities, this procedure is applied to all new developments of a certain size.

“I am very skeptical of design review processes on two grounds,” says Anika Singh Lemar, a professor at Yale Law School who is working on the Woodbridge, Connecticut, rezoning. “One, it’s hard to regulate. It’s hard to say something has to look pretty, so to get to any type of specificity you have to say it looks like stuff around it, which is a boring way to address aesthetics.”

The second, she said, is the question of motivation. America’s failed experiment with public housing is still invoked to stop multifamily development and tall buildings coast to coast (though it was not the height of the buildings at Pruitt-Igoe that contributed to residents’ sense of alienation). The conflation of form and occupants extends to smaller multifamily buildings too. “What was really driving these cities [with conservation districts], from Boise to Nashville to Charlottesville,” says Lemar, “wasn’t about what was ugly, per se. It was concern about density and increasing population.”

To understand the costs of this process, consider Seattle, where the housing researcher Dan Bertolet undertook an exhaustive analysis of design review, which applies to almost all multifamily development in the city. The city’s design review board did things like postpone the approval of a 400-unit, transit-oriented development with 168 subsidized homes because they didn’t like the color, the presence of a ground-floor day care, the shape of the façade, and the ground-floor residential units. A “passive house” project—six stories, 45 units, ultralow energy use—was required to attend a third meeting after the board asked for more bricks, though it eventually approved the building without bricks, 19 months after the builders first applied. The list goes on. Similar standards in the city’s historic districts, Bertolet calculated, had cost Seattle more than 1,000 new homes over a period of a few years—and, because time is money, driven up the cost of the ones that did get built.

Commissioners like the ones in Seattle exist in hundreds of American neighborhoods and cities. To watch them at work is like beholding an architecture-school crit in reverse: This time, it’s the architects who present their work and the nonarchitects who give the feedback. You often hear commissioners channel the user-friendly language of the city employed by Jane Jacobs, rather than the jargon of the academy. You hear about a “sense of place,” and the human scale, harmony, context, neighborhood character. Mostly, you hear the eager, constructive approach of meddle management—diktats from people who feel compelled to demonstrate the worth of their own positions through constant engagement.

On a purely visual level, the resulting architecture-by-committee averts some monstrosities while watering down other original ideas. The so-called gentrification building—the variegated façade, the quietly receding roofline, the massing as a collage of intersecting cubes in four different colors and materials—is often a response to public feedback, which boils down to: Make this building feel smaller. (For that reason, the “gentrifier” style is just as prominent in new low-income housing.)

In 2017, Bertolet suggested Seattle borrow the review structure from Vancouver, Canada, where city staff had the final say after consulting with a citizen panel (though staff reviews in places like San Francisco are hardly faster, more objective, or more transparent). “We have a housing crisis, not an aesthetics crisis,” Bertolet says now. “Giving residents veto power over design will slow homebuilding and make housing more expensive.”

The mother of all design pressure is the zoning code itself, which is supposed to protect residents from environmental hazards like slaughterhouses being built next door—but has long been used to micromanage construction down to the window glass.

Because zoning codes are both restrictive and out of date, they force many builders to seek exemptions, which often trigger design-review-style public meetings. Politicians like obsolete zoning codes, since this negotiation gives them the power to extract concessions from any project that deviates from a site’s strictly prescribed use. (In Chicago, “aldermanic privilege” has proved a little too much to handle and has led many pols to prison. Elsewhere, officials simply take bribes the legal way—as campaign donations.)

Regardless of how much you trust your local representative, this piecemeal spot-rezoning process is bad for new housing growth, since it introduces so much uncertainty and time into the development process. The understanding that zoning rules are made to be broken, meanwhile, embitters residents who double down on strict zoning. If developers consider the current zoning code a baseline, why won’t they do the same in the future?

Better zoning laws could avoid these kerfuffles in three ways. First, zoning that actually anticipates what neighborhoods need would give developers and residents a better understanding of what’s expected and permitted, building trust and obviating site-by-site stand-offs. Second, reforming the code around issues like parking and setback requirements would cease to precipitate many of the ugly designs residents say they don’t like. Third, much of what is sometimes considered an aesthetic preference—making sure a project doesn’t include a big, blank street wall, or a cavernous garage opening—can be codified rather than negotiated later.

That was the principle behind the “form-based code,” a concept established in the 1980s by the architects Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk in their plans for Seaside, Florida. Under a form-based code, zoning is not so much concerned with uses (what sense does it make to separate offices and housing when we’re all working at home now anyway?) but with appearances. Form-based codes can anticipate the prerogatives of design review from the start, including guidelines for materials, signage, windows, and other details. The system is being used to govern what gets built in places like Miami; Arlington, Virginia; and smaller New Urbanist communities.

There are drawbacks. The buildings, obviously, look pretty similar to each other. It’s also hard to build a code that vanquishes the back-and-forth. “If you could create a by-right process where you didn’t have the same argument over and over again, I’d be willing to sacrifice diversity in architecture,” said Laura Foote, the executive director of YIMBY Action, a housing-growth group. “But people just want it both ways. Having a giant code and still having a design charrette where people argue—those things are correlated!”

One of the ironies of this debate is that America’s most beloved (and sadly, most exclusive) neighborhoods were all created without much regulatory supervision. In many cities, cheap and attractive new buildings were made possible by pattern books like the Sears Modern Homes catalog, which not only showed you the design but also shipped you every last beam and bolt, a colossal Ikea set. The company sold more than 70,000 houses in 370 designs. Some were multifamily, such as the Atlanta, a Craftsman fourplex that would have provided entry-level rental units along with a steady income stream for the owner.

The idea that you could unlock economies of scale up and down the housing supply chain with simple, replicable designs was co-opted by suburban developers and deployed from Levittown, Long Island, to the exurbs of Phoenix and Houston. Prefab became synonymous with cheap, and not in a good way.

What if that strategy could also serve infill housing? Much-vaunted modular housing, while it speeds construction, has done little to ease permitting and other reviews. But other ideas are afoot. Several California companies are now competing to mass-produce accessory dwelling units, also known as granny flats or backyard cottages. Los Angeles has staged a design competition for preapproved ADU plans. As Carolina Miranda notes in the Los Angeles Times, the city already has off-the-shelf plans for fixtures such as swimming pools and staircases—and now offers 14 preapproved designs for studios as well as one-bedroom and two-bedroom units that can be installed on most of the city’s residential parcels. (Would-be builders still need to negotiate with the architects to use one of them—but at least they won’t get stuck explaining why they chose plastic siding.)

The city of Bryan, Texas, is experimenting with a similar program that aims to jump-start the construction of “missing middle housing,” the type of small, multifamily infill that once populated urban neighborhoods across the country. Bryan, which sits directly adjacent to College Station and Texas A&M University, is trying a technique called “pattern zoning.” As of fall 2020, the city has four designs on file for its Midtown area, which can be downloaded, remixed, customized, and deployed free of charge—permit included.

The designs for the Midtown Pattern Zoning, which won a charter award from the Congress for the New Urbanism, have porches and gables and peaked roofs, board siding, and white trim against darker base coats. They achieve what has been called “stealth density”—multifamily buildings that fit the mold of traditional single-family homes. If it is a deviation from context that gets neighbors riled up about new buildings, they will have little recourse to complain here.

“We’re interested in alternative models for distributing missing middle housing, because nothing we’re doing seems to be working,” said Matthew Hoffman, the Arkansas-based architect who managed the project and designed the preapproved houses. “Much as I am frustrated by NIMBYism, it’s incredible pernicious, but they have a point that most of the stuff that’s been delivered just fucking sucks.” He is bothered by the notion of “neighborhood character” being some kind of proto-racist term: “Actually, it’s a really good idea! There are beautiful neighborhoods in this country that are both diverse and beautiful. The idea that it’s something that happened in the past that we can’t do anymore? That’s incredibly sad.”

Even a well-intentioned code, Hoffman said, is full of rocks upon which the ship of good design can be dashed. The easiest path through competing requirements never produces the best building, and that’s before neighbors have their say. With these blueprints, Bryan is giving would-be builders a map. “We want people in the neighborhood to have the tools to participate in the growth of their neighborhood, literally. All the people who walk around and say, ‘Somebody oughta.’ ” The people for whom navigating the code and hiring an architect might be too much. The designs are right here.

Bryan developers are still welcome to go the conventional route. “All we’re saying is: If you want an expedited permit and a free design, this is how we’d like you to do it.” Does it sound like a cookie-cutter design? It is. But it’s quick and it’s handsome. You can have your cookie and eat it too.