Of all the mistakes made by city planners in the postwar era, the passion for highway construction has to be one of the most foolhardy. After the early success of systems like the autobahn and freeways, cities everywhere were carved up to make way for giant roads, crashing through neighbourhoods and creating opportunities for “comprehensive redevelopment”.

This was considered progress, a necessary part of entering the modern world. But some strange things happened – the most damning being that these new roads didn’t reduce traffic at all. Instead, they induced demand, clogging up almost as quickly as they were built. As time went on, communities began rejecting the plans and fighting back against the bulldozers, halting development in its tracks and kickstarting the modern conservation movement.

Finally, the knockout blow was the oil crisis of the 1970s which put an end to many big plans. Looking back, we can marvel at how outrageous some of these and later schemes were, and the traces they left behind.

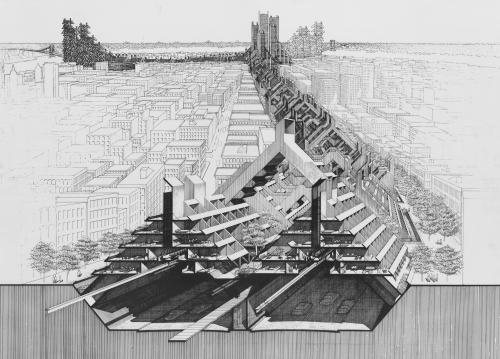

Lower Manhattan Expressway

The classic evil mastermind of road building is Robert Moses, the New York official who planned and built huge amounts of infrastructure, but destroyed many tight-knit communities in the process. Included in his grand plans was the Lower Manhattan Expressway (Lomex), which would have sliced directly through the Lower East Side, evicting nearly 2,000 families.

A vigorous local campaign from the early 1960s involving urbanist Jane Jacobs managed to hold off and eventually cancel the project, saving the neighbourhood from the wrecking ball. But Lomex has since become a source of nostalgia through the plans by architect Paul Rudolph, showing vast brutalist housing blocks snaking along and above the roads.

Spadina Expressway

In 1968, Jane Jacobs moved from Greenwich Village to Toronto, but didn’t slow down on her activism. She quickly learned that her new home was to be demolished for the Spadina Expressway, which would join the city centre to the growing suburbs.

Jacobs was involved in the campaign to halt it – a battle partly between those who had moved out and who stood to benefit, and those who still lived in the centre and were at risk of having their communities physically destroyed. By the time the anti-road campaign won, a short stretch of the expressway had been completed, but the neighbourhoods in its path were spared.

Marina Freeway

Holding a claim to being perhaps the world’s shortest working highway, the most westerly portion of California State Route 90 was originally part of a giant road planned to cut right across Los Angeles, the spiritual home of the traffic jam. Again, the strength of community resistance meant that the plans were reduced until all that was constructed was a short spur a few kilometres long. It held the dubious honour of being named the Richard M Nixon Freeway for a few years in the early 1970s.

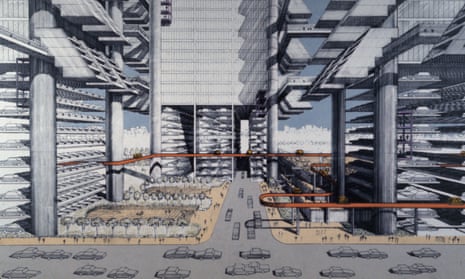

Fitzrovia Masterplan

The UK government’s Buchanan report of 1963 looked at the US and wondered what was going to happening to British cities as car ownership took off. Proposing a variety of different systems for accommodating traffic in towns, they demonstrated a wild plan to flatten much of Fitzrovia in London and create a hexagonal network of major roads, with new offices and residential spaces stacked above. It never happened, but it became a blueprint for redevelopment across the country in the following generation.

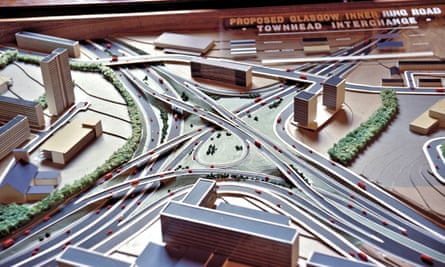

Glasgow Inner Ring Road

Glasgow was the UK city perhaps most gouged by highway planning, with a remarkable stretch of the M8 motorway smashing straight through the tenements of Charing Cross, complete with “bridges to nowhere” and other infrastructural detritus. But what was built was less than half the original ring road plans that would have run through Glasgow Green and right past the 12th-century cathedral. The results of the first stages, complete by the early 70s, helped galvanise public opinion against the project. In the end the east and south sections were abandoned.

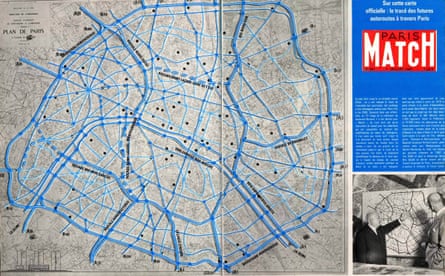

Plan Pompidou

Paris nearly suffered a repeat of Baron Haussmann’s boulevard gouging in the 1960s, as Georges Pompidou attempted to make the city “adapt to the automobile”. The banks of the Seine were turned into expressways, but many planned radial roads were thankfully left on the drawing board, and the right bank of the river is to be fully closed to vehicles in the future.

Foreshore Freeway Bridge

One odd monument down by the harbour in Cape Town is a set of two concrete flyovers that spring out of the Helen Suzman Boulevard before abruptly ending, leaving their swooping sections dangling in mid air. They are the remnants of a plan for the Eastern Boulevard Highway, abandoned in the late 1970s for lack of funds and demand. A symbol both of municipal hubris but also a local landmark, it was adorned with “The World’s Largest Vuvuzela” for the World Cup in 2010.

North Western Expressway

Planned from the early 1960s, the North Western Expressway was intended to run from central Sydney to the mountains in the west, but heated protests meant that only a few short sections were ever built, leaving most of the route an empty channel of land. One odd result was the massive Gladesville Bridge, at the time the longest concrete arch ever constructed, which forms part of the few kilometres of the road that was actually completed.

Olimpijka

Since the second world war plans had been afoot to construct a large-scale road that would run across Poland through Warsaw, linking the German and Russian borders. But it wasn’t until the run-up to the 1980 Moscow Olympics that work began, stopping due to lack of funds after only short sections were completed. The fragments became known as Olimpijka, and were a pilgrimage spot for urban explorers before eventually being destroyed when the road was finally completed as the A2 in the early 2010s.

Borovsko Bridge

Begun after the German annexation of Czechoslovakia, the Borovsko Bridge wasn’t completed until 1950 in the newly communist republic. The highway itself leading south from Prague was never finished, leaving the bridge marooned. Its huge concrete span was gradually submerged by a hydroelectric project, to the point where just the road surface stands above the water.

A4 Netherlands

Part of the highly developed Dutch road system, route A4 sweeps down from Amsterdam to the Belgian border on the way to Antwerp. It passes through Rotterdam where, embarrassingly, a cloverleaf junction lacks its fourth wing. To this day a 20km stretch of the route remains unbuilt, leaving a suspiciously empty patch of land between residential neighbourhoods waiting to be unified.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, and explore our archive here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion