“They are designed to make automobile collisions impossible and to eliminate completely traffic congestion.” Norman Bel Geddes, Magic Motorways, 1939.

“[It] has the great potential to enhance public safety and mobility, reduce traffic congestion, and advance transportation efficiency…” David L. Strickland, Counsel, Self-Driving Coalition for Safer Streets, 2016 Congressional hearing.

While these two quotes are largely interchangeable, they describe two different technologies in two very different eras. If you switch the publishing years and the technology named, many articles extolling the virtue of automated vehicles (AVs) would be remarkably indistinguishable from those supporting urban freeways decades ago.

The rise of urban freeways offers a number of lessons on how to manage new transportation technologies. AVs promise changes on a wide scale and, depending on how they are rolled out, could have positive or negative effects on communities and the environment.

When the Interstate Highway System was first proposed, there was serious need to upgrade the country’s road infrastructure. Although the automobile was engineered to travel quickly, cars were inching along roads initially designed for horses and carriages, and adapted for cars haphazardly and unevenly.

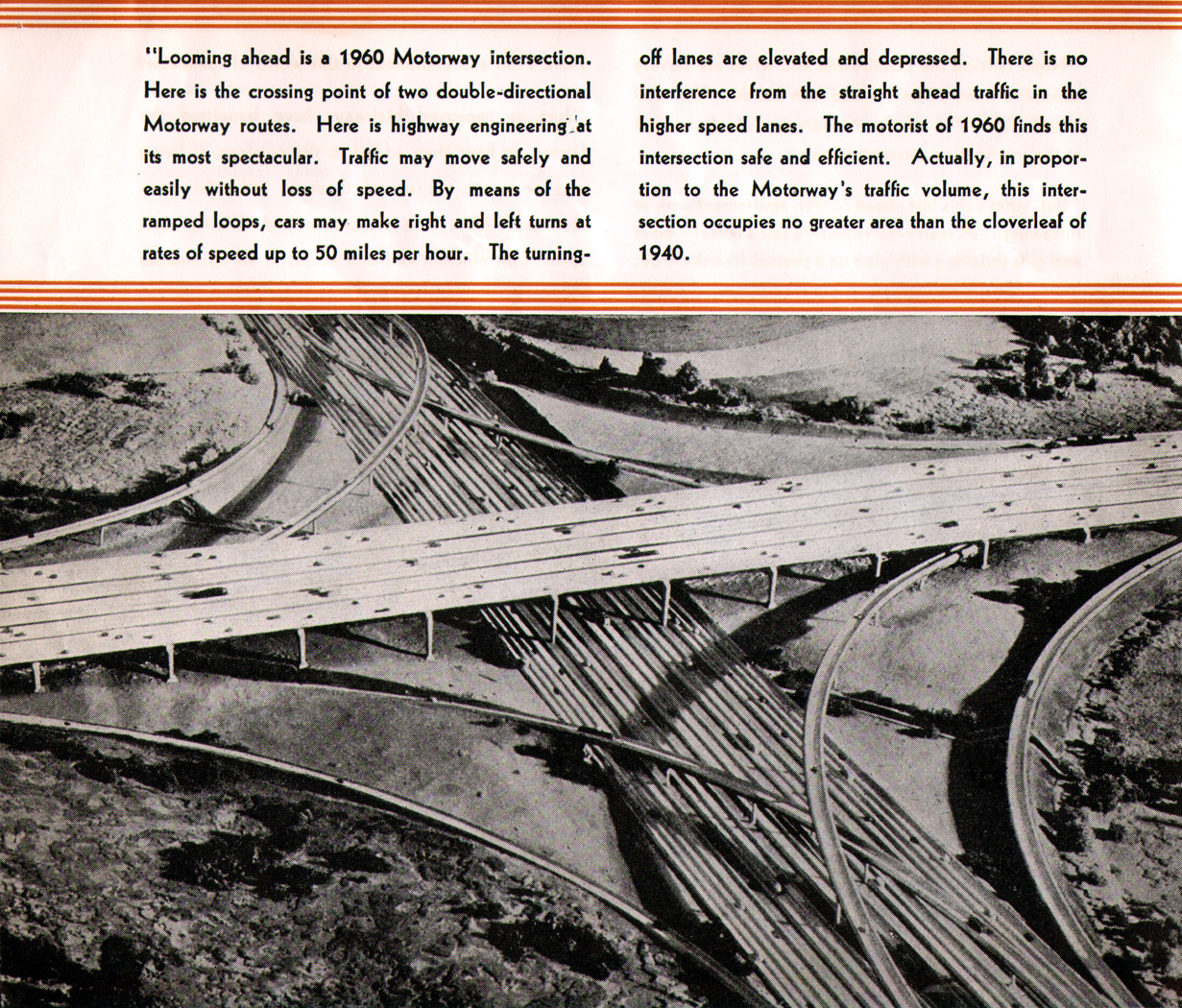

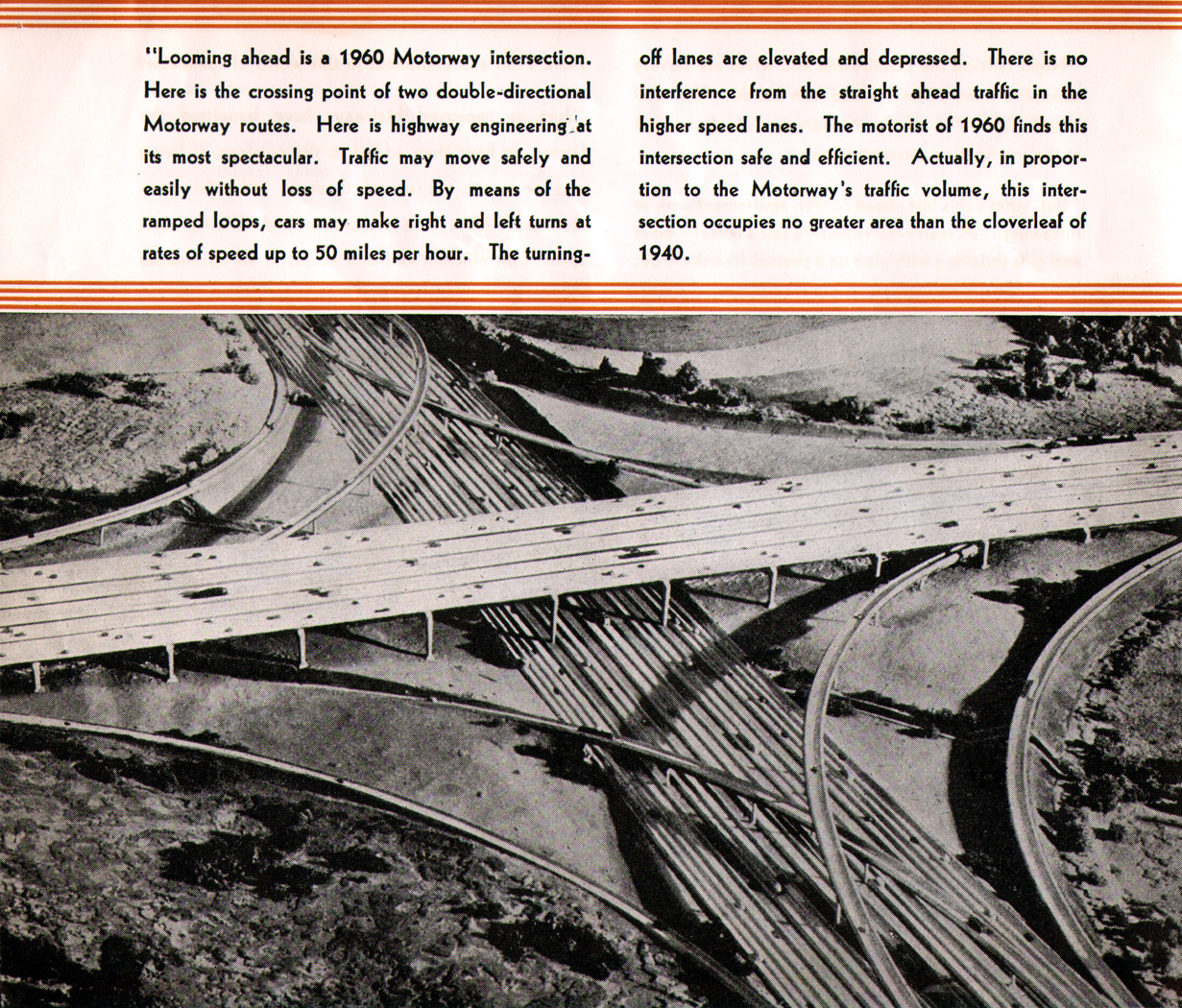

General Motors seized on consumers’ discontent when planning its Futurama exhibit for the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. Five million visitors waited in long lines, to experience Futurama, which took patrons on an amusement park style ride through a miniature “city of 1960.” Attendees were enraptured by the promise of new freeways designed specifically for cars. The elimination of stop and go traffic made the exhibit especially attractive to Americans just emerging from the Great Depression – much like Americans today excited by the prospect of AVs ending traffic headaches.

General Motors seized on consumers’ discontent when planning its Futurama exhibit for the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. Five million visitors waited in long lines, to experience Futurama, which took patrons on an amusement park style ride through a miniature “city of 1960.” Attendees were enraptured by the promise of new freeways designed specifically for cars. The elimination of stop and go traffic made the exhibit especially attractive to Americans just emerging from the Great Depression – much like Americans today excited by the prospect of AVs ending traffic headaches.

Engineers and planners of the era posited that, by speeding access to downtowns and simultaneously allowing others to bypass them, urban highways would keep city cores viable in the coming freeway age. Beltway style highways were prescribed – even around small downtowns – in order to ‘protect’ the traditional downtown areas, not destroy them.

For example, in Fort Worth, Texas, a downtown loop was prescribed to make downtown a place where “the pedestrian would be king” in 1953. In practice however, urban freeways tended to work in opposition to the small block-sizes, diffuse street networks, and mix of shops, homes, and offices that make neighborhoods thrive.

For example, in Fort Worth, Texas, a downtown loop was prescribed to make downtown a place where “the pedestrian would be king” in 1953. In practice however, urban freeways tended to work in opposition to the small block-sizes, diffuse street networks, and mix of shops, homes, and offices that make neighborhoods thrive.

While urban highways made the post-war American dream of home ownership accessible for many families, by fracturing communities and lowering home values, urban highways generally eroded – rather than strengthened – central neighborhoods.

The unintended environmental costs of urban freeways were also significant. The development of highways allowed metropolitan regions like Philadelphia to expand rapidly outward, despite only modest population growth. Highways enabled people to live farther from their workplaces, travel further in their cars, and thus release more greenhouse gases and other pollutants into the air.

In recent years, policymakers have acknowledged the unexpected environmental, social, and economic costs of urban highways and reversed course by providing more transportation choices and walkable developments. Some cities have spent huge sums of money to remove or retrofit urban freeways. Boston’s “Big Dig” submerged its downtown highway underground, while San Francisco deconstructed the highway that had long separated its downtown from the waterfront.

Clearly, momentum for smarter, more sustainable communities is growing, but enthusiasm for AVs threatens to derail this success. Without learning from the pitfalls of our eager embrace of urban highways, communities may make the same mistakes again.

When autonomous vehicles appear on roadways in the next five to ten years, they will bring numerous benefits. They will eventually prevent 90% of car crashes and provide much needed mobility to elderly people, those with disabilities, and those too young to drive. Platooning and vehicle design changes could markedly reduce per-vehicle greenhouse gas emissions, and car-to-car communication could ease congestion. Supporters of AVs cite these and other factors to argue that self-driving cars will make travel easier, safer, faster, and more comfortable for all.

While these potential benefits cannot be overlooked, AVs – like urban highways before them – will create new and unexpected challenges as well. Each benefit has the potential to spur secondary effects, some of which will negatively impact the environment or peoples’ lives. Opening mobility up to more people could mean more travel and thus more wear and tear on the roads. If cars remain powered by fossil fuels, more travel will mean more carbon emissions and air pollution. Faster more comfortable travel could also lead to unprecedented suburban growth. The seductive convenience and speed of AVs could dampen public support for sidewalks and cycle lanes, which nudge us to live healthier lives.

Luckily, we have been here before and we have the opportunity to learn from our past. We have been swept up in the excitement of a new utopian technology before. We have tried to design our communities around this new technology and, slowly but surely, have spent decades working to rebuild cities around people rather than technology. AVs can and should be a part of the future, but let’s learn from our past and continue designing our communities for people. In other words, we should treat vehicle automation as a means to an end rather than an end in itself.

In that vein, there are some steps planners and community leaders can take now to harness the benefits of autonomous vehicle technology and avoid the costly errors of the past. Planners should rethink minimum parking requirements now since AVs could reduce parking demand by as much as 90%, opening up a lot of space for parks, affordable housing and private development. Communities should start managing their curb space now because AVs, much like ride-sharing services, will depend on this publicly-owned space for pick-ups and drop-offs. Finally, AV technology should be used not only for cars, but also buses, shuttles, and paratransit services. Leaders could quickly take advantage of the dramatically lower operating costs of autonomous transit to draw in new riders with frequent, fast, and cost-effective BRT lines and neighborhood shuttles.

Overall, autonomous vehicles could make travel safer, cheaper, and more comfortable for many people. However, just like highways before them, AVs are not the silver bullet for our transportation challenges. While highways have made travel between cities cheaper, faster, and safer, they levied numerous unintended costs, especially in urban areas. Autonomous vehicles will similarly have mixed impacts. Community leaders should not plan around them, but instead determine how they can help them build places that better support public health, vibrant economies, healthy ecosystems, and quality of life for all.

Will Leimenstoll is an urban planner, writer, and researcher who focuses on equitable development and the future of transportation. He is currently an ORISE research participant with the Oak Ridge Associated Universities (ORAU) based in Washington, D.C. The opinions provided in this post are his own, not those of ORAU, which funds his research fellowship.

General Motors seized on consumers’ discontent when planning its

General Motors seized on consumers’ discontent when planning its  For example, in Fort Worth, Texas,

For example, in Fort Worth, Texas,