For years a graffiti message has appeared throughout San Juan, Puerto Rico’s capital, as an urgent demand: Dragado ya! (meaning “dredging now!”).

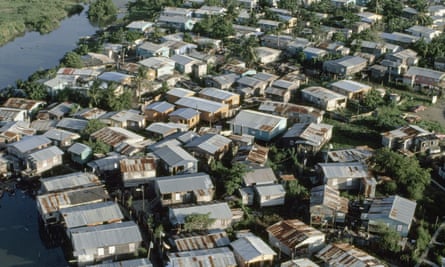

Even passersby who have never set foot in the eight barrios making up the Caño Martín Peña community – a large informal settlement along 3.75 miles of canal in the central city – know the message points to the dire need to dredge the waterway, which has become so clogged with refuse that those driving by with the windows down can immediately smell the stagnant waters.

This previously neglected area was originally established on mangrove wetlands and lacks adequate water drainage systems, so even mild rain storms led to flooding that backed up sewage and polluted waters, causing health and environmental problems for its 26,000 residents.

Desperate to alleviate these issues, the local community started organising themselves to demand the dredging of the canal, but feared the rising land values and displacement of families that such neighbourhood improvement tends to bring.

Residents spent two years collectively drawing up plans for the future of the area, ultimately creating a formal development and land use plan which was then adopted by the Puerto Rico planning board. With the help of national and city government support, local residents and organisations set up a collaborative project called Enlace to help implement the plan to improve the canal and its adjacent communities in an inclusive way.

A crucial part of this involved the establishment of a community land trust, to inoculate against gentrification through collective ownership of land. The 2,000 families of el Caño – as the area is locally known – now collectively own 200 acres of land that cannot be sold.

As part of the wider Enlace project, residents are involved in decision-making in the social and environmental transformation of their area, and are able to feel more secure about their future as landowners.

Citizen participation and critical awareness has been fomented through various programmes: addressing and improving environmental justice, affordable housing, food security, violence prevention, local entrepreneurship, youth leadership and adult literacy.

The bonds within the community are evident the moment you step foot in the neighbourhood. On a recent afternoon, resident Carmen Febres pulled her car alongside two teens riding their bicycles and asked them if they had done well in school that day. “Sí,” nodded the boys in deference. She wagged her finger at them, “I’m keeping an eye on you!” As they pedalled away, they seemed to like her admonishing attention.

Every bit a leader, Febres is president of the G8, an umbrella organisation of the eight barrios, which operates under a pluralism recognising their common interests while respecting the political, religious or cultural diversity among them. The G8 works in tandem with the community land trust and city government to progress the Enlace project, ensuring that residents have a say in all aspects of decision-making in the project.

Community gardening has been a central activity in the district, helping facilitate youth leadership and improving food security, as well as enhancing education about sustainable food. There are several communally managed urban gardens in the district and more across the wider city – all of which are seen as a response to the fact that 85% of food is imported in Puerto Rico.

These activities have helped the community become a model of self-improvement and sustainability, as well as fostering pride and a more secure sense of belonging among residents. It’s attracted international attention too: last October, the project was awarded the 2016 United Nations World Habitat Award.

Genesis Colón, 20, traveled to Quito last October for the awards as a member of the project’s youth leadership development group. The third of four siblings, she is studying nursing and is the first in her family to pursue a university degree. Colón says she wants to “see through to the future, to the dredging, and to struggle for the community”. She adds: “My family has considered leaving Puerto Rico, but I want to stay.”

This is no small commitment in a country facing a historic $72bn debt and economic collapse. The impetus to leave at this time is strong, with emigration levels rapidly increasing (84,000 people left for the US mainland in 2014-15), further eroding the tax base and in turn deepening the crisis. The US Congress has imposed a federal fiscal control board on Puerto Rico – a US territory of 3.4 million people – now poised to enact austerity measures that will likely eviscerate the public sector.

A sizeable portion of the debt is owed to predatory US vulture hedge funds – two US Supreme Court rulings nullified Puerto Rico’s supposed autonomy as a US commonwealth, exacerbating Puerto Rico’s colonial condition. At the same time, local laws designed to create a tax haven for the mega-wealthy are luring outside speculators.

This is a menacing prospect for communities without the kinds of protections that the Caño Martin Peña’s G8 have forged. “It’s easy for communities to lose control for not having the right piece of paper,” says David Ireland, director of the Building and Social Housing Foundation, which partners with UN Habitat to organise the World Habitat Awards. He adds that using a land trust to deal with speculators picking off members is not usually seen outside a highly developed context. “While not a guarantee, it offers a level of protection, and gives a community a fighting chance to stay where they belong.”

The community land trust also helps sustain the area by generating income through renting its properties, developing vacant lots and implementing various projects. Individual houses can also be sold, with a right to use the community-owned land they stand on.

Building community trust, especially in such a climate, has been a key achievement on both macro and micro levels. Perhaps the project’s most delicate programme involves relocating families whose homes are most prone to flooding or stand in the way of dredging. Integrating members of 130 families who have already moved to coach residents facing relocation has been key to its success, according to Lyvia Rodríguez, who directs the Enlace project.

In her view, the challenge is to create hope for the society and country as a whole, with environmental policy positively influencing economic advancement.

With more than 100 collaborators and allies, from university oral history projects to solidarity with other community struggles – such as the activism combating disposal of toxic ash in Peñuelas to the country’s south – a spirit of exchange has flourished.

This kind of vision has attracted Line Algoed, an urban anthropologist from Belgium, to work with el Caño. She aims to establish an international observatory of popular knowledge on community land trusts in informal settlements, “so community leaders in so-called ‘slums’ around the world can find their way to the Caño to exchange information with people like Carmen Febres, to get this model translated to other communities worldwide”.

To share this land trust and development model with communities worldwide, a group of about 20 people from NGOs and community enterprises in Latin America, North America and Europe will visit el Caño in February.

Algoed also sees an important shift in moving away from the emphasis on individual land titles in regulating informal settlements, towards collective land ownership as a more effective protection of historical and cultural communities. She says the project also sets an example for architects and engineers to participate in community initiatives rather than hope to win the interest of members without that grassroots work.

Ireland shares such a holistic view in promoting not just the community, as if in isolation, but in relation to the rest of the city. “When poor people get displaced,” he says, “they often become the poorer for it, and continued displacements worsen city life as a whole. A mixed city where everyone benefits makes for a healthier social fabric.”

The graffiti messages throughout San Juan show that while community development is flourishing, environmental progress is slower: the government keeps postponing the dredging of the canal – with an estimated cost of hundreds of millions of dollars – due to the country’s ongoing financial crisis.

Still, just a few steps from the Sacred Heart University train station in the teeming Santurce area of San Juan, with the tall buildings of The Golden Mile banking district looming in the background, one can now sense change in the air at el Caño.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook to join the discussion, and explore our archive here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion