Cities define modern life. They make more money than other places, demand more of the people who live in them, and provide more for them too. Except for the people who aren’t making money; and if you are the kind who does make money, you probably know little about them. Several million humans penned together in an unfeasibly small space, and compelled to make life work. “There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city,” Jane Jacobs, the urban activist, once said. “People make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.”

Her words are pertinent given the government’s intention to build up to 14 garden villages, plus larger garden towns across England, each created as “a new discrete settlement”. Here at last is a theoretical blank page that gives communities the chance to think about what a city or town should look like.

Cities developed in the UK as a result of the industrial revolution, and some things have changed surprisingly little. A traffic jam, that modern peril, could wreak havoc for hours in 1749. Nearly three centuries on, streets are still cleaned mostly by a human with a broom and there are still more people than places for them to live. But now stop the clock. Design a city from scratch.

Here is the necessary acreage, and here is a serviceable budget. Where would you start? Would you build roads straight or curved and how many coffee shops would your high street have? Come to think of it, does a city need a high street? Just for a minute, imagine what you would like to see. There could be community-owned pets that the lonely could walk or love, sheltered park benches that turn into divans for those in need of a bed, refuges and freecycle joints, vertical transport solutions (lifts) and universal stairlessness to render accessibility inarguable. And maybe the best answers would lie in small, simple considerations – in evolving our own behaviour, laying new traditions to take care of ourselves, each other and our homes. And maybe, so that loneliness isn’t stigmatised as antisocial, there could be a sign that reads: “It’s OK to feed the pigeons.”

Paula Cocozza

Architecture

The garden cities of the early 20th century, and the new towns of 1945-1979, have followed the fortunes of the country, making it impossible to generalise about them – Peterlee, Cumbernauld, Milton Keynes and Hatfield are not much alike.

A key concept of the original garden cities was collective ownership, with them owned and managed by some sort of community trust for the benefit of residents, rather than in the hands – and for the benefit of – developers such as Persimmon and Barratt. This was mostly honoured in the breach in the first generation such as Letchworth or Welwyn. But today, a garden city could be run as a Community Land Trust, a form of ownership that contains clauses against speculation, stopping cities becoming middle-class commuter towns and ensuring their original intention – places without hierarchies, slums, “luxury living” colonies or class distinctions.

However, co-operative or community ownership is usually elective, favouring enthusiasts and those with time on their hands. The new city should aim for the universality that council housing once provided, through a system of housing allocation that would make housing accessible to anyone that wants it. The best model for this is still renting through the local authority.

The “garden” part of the garden city was not about private gardens – though in the new towns, most people had these – but about public spaces, whether the tree-lined Broadway of Letchworth or the free-flowing green spaces of residential Milton Keynes. These are the main things lacking in all new development in Britain, from the towering, “stunning developments” in London and Manchester to the looping, car-centred closes of the average suburban development, all of which take a steamroller approach to topography. Imaginative landscaping can give a place a distinctive identity, much more than the facile “traditionalist” application of Georgian pilasters and tiled roofs, creating compositions in the landscape that town planning here was once noted for, but has long since lost.

What we should expect of a new town planned in this way is that it doesn’t look planned by developers, but for the public good. Stylistically, it would make little sense to be too prescriptive. It should somehow be able to combine a cohesive look – so that it feels part of a wider whole (Newcastle and London do this with their transport networks, Milton Keynes with its stone underpasses, Cumbernauld with its rocky landscaping) – with a certain amount of experiment. Probably the best approach to this is to let the various stylistic factions of the architecture schools have their own showcases – neo-brutalists who want heroic complexes of walkways and streets in the sky, such as Bjarke Ingels’ recent work on the outskirts of Copenhagen; classicists who want Chipperfield-like colonnades around formal squares; self-build cultists who would prefer a scaled-up version of the homemade homes built by Lewisham residents in the 1980s, or in Almere in the Netherlands today – all of them could, and should, be part of a new town. All of this would be made much easier through public ownership and, as John McDonnell recently suggested, publicly owned direct labour organisations, than under the yardsticks and value engineers of the volume builders.

One constant throughout should be a showcase of technological and ecological ingenuity. It is wasteful to build, as we currently do, from breezeblocks and concrete frames that are then clad in brick; saner methods of carbon-neutral construction have been available for some time.

All of these things are wholly possible, and elsewhere in Europe, rather conservative. And if the plan is to expand the south-east of England yet further, we need to do it, and fast. But in a country as imbalanced as ours, to build new towns from scratch in the south, when streets remain empty in a city as magnificent as Liverpool, is trivial.

Owen Hatherley

Culture

Cultural planning usually involves exploiting the heritage and resources of existing urban areas, but a blank slate has its own advantages. A new city should begin by establishing flagship arts venues, whether publicly funded or in partnership with business. Obviously a museum, theatre, gallery, cinema and concert hall in the centre. Possibly an arena further out that could attract bigger artists and become a magnet for music fans in the region. These are the basics.

Equally important is the creation of a town-centre cultural quarter, perhaps near the university, where the clustering of smaller, cheaper venues such as arthouse cinemas, cutting-edge theatres and intimate performance spaces enables networking and collaboration as well as attracting tourists. In such areas, bars, cafes and clubs bring creative people together and lead to a city generating its own art. Official initiatives such as public artworks or a community festival can help to establish the quarter’s reputation as a hub of creativity and entertainment. As the city organically develops its own identity, new venues and cultural centres should cater to the needs of specific communities, ensuring diversity and social inclusion.

Cultural planning should be based on the broadest possible definition of culture, for example valuing nightclubs as highly as classical musical concert halls. With nightlife in particular, authorities and promoters should maximise the cultural and economic benefits by working as collaborators rather than foes. A liberal licensing regime should be baked into the planning process so that clubs can’t be threatened with noise complaints from residents, while the canny location of loud venues would minimise friction in the first place. You could even create a specialised nightclub quarter.

The biggest challenge for cultural planners is how to sow the seeds for residents to produce their own work. Nothing is more beneficial to a city’s cultural identity than the ability to foster its own scenes – consider Manchester in the 80s – and such efflorescences of creativity depend on the ability to survive cheaply. Without affordable flats to live in, studios to work in, and venues in which to socialise and showcase their work, young artists in any discipline can’t grow.

A persistent irony in existing cities is that thriving cultural quarters tend to drive up residential and commercial rents, forcing out the young, creative people who made them what they are. In order to preserve existing areas from extreme gentrification and enable new ones to flourish, the new city needs to prioritise affordable housing, rent controls, community arts facilities, grants and progressive licensing laws. You can’t manufacture an internationally famous music scene or visual arts boom from the top down, but you can remove many of the obstacles that make their evolution more difficult. Twenty years into the city’s life, the most culturally dynamic area might be one that the planners never even considered, but one that their foresight ultimately made possible.

Dorian Lynskey

Transport

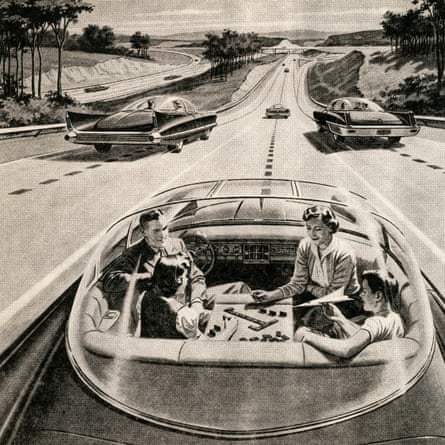

On reaching the boundaries of a fantasy modern city, the first thing visitors should be required to do is check in their car keys at the gates. Electric vehicles are tolerated where mobility demands it; for families, the disabled, or for deliveries. Driverless pods are legion. But there is no place for the diesel car, or older gas-guzzlers. The air is clean and the streets uncongested. At least, for now.

Creating some sort of rail-based mass transit would be essential, according to David Metz of the Centre for Transport Studies at University College London, a former chief scientist at the Department for Transport. “It gives you speedy travel in a city, where roads would quickly become congested.”

A new, fully automated underground system just below the surface – or even elevated for the views in places – might be slightly more costly to build than a tram network, or an electric bus rapid transit system with dedicated lanes. But the latter, Metz says, requires wider streets. “You want the good interaction between people, the buzz of city life, the social, financial and cultural agglomeration benefits. Boulevards create severance between people.”

The city centre would have narrower streets, populated by pedestrians, cyclists and fleets of self-driving pods, free to use on set local routes, and cheaper than taxis when summoned on demand. The new city’s streets are pre-mapped into autonomous vehicles, and its infrastructure built with them in mind. Manufacturers finally see a place where driverless technology can quickly embed and flourish, with grateful residents freed from the expense and hassle of car ownership.

On suburban roads, incentives for pooled, electric vehicles help reduce congestion. Buses run on electric, gas, or human waste, pioneered by Bristol’s poo bus. Commercial, construction and emergency vehicles are still needed, but with few private cars parked on roadsides, the city has ample room for dedicated, joined-up cycle lanes.

But the city needs variety and character too: let’s have some inexplicably curvy roads, and for-the-hell-of-it expensive flourishes in station buildings, making them attractive places to meet and be. Should the new city be constructed in the kind of hilly landscape enjoyed by the likes of Sheffield, build funiculars, or even a cable car of the type championed by Boris Johnson; a concept, says Metz, that only failed in London by being in entirely the wrong place. In dense, high-rise parts of city, lifts will be “the ultimate transport system for an ageing population”.

Planners should heed the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, which counsels that the most sustainable form of transport planning is to persuade people not to travel in the first place. Now that most work no longer needs to be hived off into industrial estates, attempting to design a city that blends the residential and the workplace may help cut commutes.

Yet ending all traffic may be no utopia. “Congestion is a mark of success,” adds Metz. A booming metropolis, where more people want to work and live, will see ever more strain on the transport network. At some point, commuters to our ideal city may still have to suck it up.

Gwyn Topham

Politics

Any city built from scratch, with any ambition, assumes the participation of its inhabitants, assumes neighbourliness, a “sense of community”, as its raison d’etre. In architectural drawings, this is conveyed by a man on the street, mending a bike, plus a child carrying balloons. On the BBC, the “community” is religious leaders, plus or minus a do-gooder who runs marathons. None of these cut it: the only thing that meaningfully unites people who live alongside one another is wanting certain things – improvements, activities, visual interventions into unloved spaces, places for young people that aren’t bus shelters, but also bus shelters – for their area. This is politics.

The peculiarity of modern politics is that all central governments claim to want devolution, or its more fashionable, radical cousin, subsidiarity (the delegation of decision-making down to the lowest level at which it could be made), but then squeeze budgets so hard that local bodies are left with the “choice” of cutting all their children’s centres, or three-quarters of them, plus meals on wheels. For local democracy to be meaningful, its decisions have to be actionable and its statutory duties (providing housing for the low-waged, for instance) have to be doable. It can’t just be lurching from one crisis to another on the back of some hokey PFI deal.

Money is necessary but insufficient: the appetite is there for civic congregation – as you can see when a hospital is threatened with closure – but what alienates people is threefold. First, cliqueyness, jargon, the fear of arriving at a conversation that’s already been going on for 15 years, and looking foolish. The second is the joylessness of civic space. The third, the sense that the invited conversations are usually boosterish, anodyne (tell us what’s great about your borough!), deter rather than invite change, have no route to change anyway and avoid difficult topics.

Urban utopias take time: you can’t participate civically if you’re spending half your wages on rent, and this is ultimately about land value. But, deeper than that, there’s a question that slipped out of all political language at around the time the language of opportunity came in: what are conditions like at the bottom? Leave aside: How easy is it to escape poverty? How is life in poverty? Are you working 18-hour days? Are you atomised by your own tiredness? Is participation on a list of impossibilities a long way below a holiday? It’s important that civic spaces are not only open to a leisure class, or they lose their lustre for everyone.

Zoe Williams

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion