We’ve seen the road-straddling bus that glides over lanes of traffic, the high-speed transport pods of the Hyperloop, and bike paths in abandoned tube tunnels. Now here’s the latest radical transport idea to transform our cities: putting cars in tunnels – but with a twist.

Dreamt up by Lars Hesselgren and his research team at London-based architecture practice PLP, and announced today at the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, the CarTube proposal reflects the company’s motto: “Streets are for people, not cars.” The solution to achieve this? Move a city’s cars underground on to a network of tracks in small-bore tunnels, creating more safe space at ground level for bicycles and pedestrians.

Sounds rosy, but there are a few technical issues to surmount before this vision can be realised, especially in London, its case study city. First, as a fully automated system, it would rely on only electric, internet-enabled vehicles using it. As it stands, fully electric cars only make up a tiny proportion of the cars on the road – although at last year’s UN climate change meeting in Paris, the UK – along with Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and others – agreed to ensure that all new cars will be zero-emissions by 2050. Which, admittedly, is 34 years from now.

Second, building an entire network of new underground tunnels takes time, space and money. We know from London’s Crossrail just how expensive creating even a relatively simple underground tunnel route can be – though PLP insists the CarTube tunnels are far cheaper because they’re smaller, don’t require large stations, and have no need for ventilation because there will be no vehicular emissions. Still, in a city like London, with tube tunnels, train tunnels and sewerage systems, it’s anyone’s guess where the subterranean space for the CarTube network would even be found.

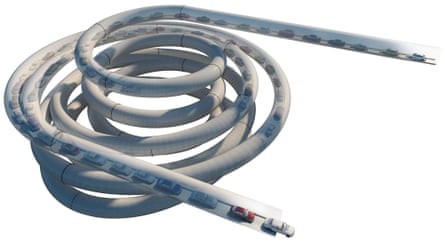

The specifics of how the system works remain a little hazy, but here’s the general idea: the CarTube grid of subterranean tunnels would link to a city’s existing road infrastructure, with entrances feeding in from periphery motorways as well as simple ramps throughout the city. Once in the tunnels, the cars would automatically move at a steady, continuous rate, evenly spaced from one another.

Users decide exactly where they want to start and end their journey, book a time slot, and the system does the rest – whether you’re using your own car or a taxi. Vehicles are spaced at two-metre gaps and locked into position on constantly moving tracks, so accidents and delays are also prevented.

Furthermore, if you arrive at your destination by private car, you could take a pedestrian lift to the surface while your car is kept in a “car stack” – like an underground car park with an automated valet service. Later, your car would be returned to you on demand.

In the London case study, PLP claims travel times on the CarTube would be roughly a quarter of what is achieved on existing roads, with a typical journey from Heathrow to the City of London taking only 14 minutes (the same journey on Crossrail is due to take 34 minutes).

As with all elements of the “smart city”, the objective here is to eliminate disruptions and inefficiencies from urban life. The CarTube envisages replacing the current “stop-start model” of urban transport – be that traffic lights or train stops – with a “fluid, integrated network”. It’s this idea of an interruption-free journey that leads to PLP calling the CarTube “the next best thing to teleportation”. They claim it will reduce urban travel time by 75%.

“The real issue is control,” Hesselgren explains. “Trains and tubes have controls; cars don’t. Autonomous cars do, but they don’t work well with pedestrians, cyclists and other unexpected elements. The only way you can have a high-capacity car network in a city is to have a dedicated track.” He insists the idea is not repeating the “awful” underground motorways of the latter part of the 20th century.

But shouldn’t we be thinking about moving away from car-based city transport altogether, rather than simply building expensive alternative infrastructure for it? What about promoting cycling and public transport? “This is public transport,” insists Hesselgren, adding that because cars on the CarTube can be continuous and closely spaced, moving at a speed of 50 miles per hour (80kmh), capacity for transporting people is higher than packed trains that come every five minutes.If the project’s goal is to reduce street-level congestion, then is a city like London (which already has an extensive public transport system and congestion charge) its prime target? “London is our case study, but chances are it will get built somewhere else where people are desperate for a solution,” Hesselgren says, listing Mexico City, Delhi, Jakarta and Mumbai as the sorts of gridlock-heavy cities that could benefit from the CarTube. “This kind of approach in those places could really make a difference,” he adds. That difference, however, would rest on the replacement of all cars in those cities with fully automated, emission-free vehicles – which seems a long, long way off.

It is easy to come to the conclusion that this would never work, let alone happen, so why dedicate attention to it? Putting aside the key lesson from this year that you should never underestimate the potential of something that seems so wholeheartedly preposterous, proposals like the CarTube reveal how we are responding to the mounting crisis of urban transport and what we want out of the future city. Now might be the time to mention that the CarTube team is meeting with potential collaborators, including Google, in the new year to move the idea forward.

As we reported earlier this week, some cities are tackling street-level car congestion with approaches far simpler, and cheaper, than an entirely new automated underground transport system: building safe segregated bike lanes, controlling car access to urban cores, and increasing the capacity on public transport. Taking cars off the road is a noble idea indeed, but putting them underground may not solve the transport challenges our cities currently face.

What do you think about the CarTube? Share your thoughts in the comments below and follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook and join the discussion

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion