I have started a list in the back of a notebook, a short dictionary of the language of gentrification. It began with the word “decanted”. Typically we decant wine from a bottle into a carafe in order to separate the sediment. Increasingly I’m noticing it in reports of council estates being bulldozed, their residents being “decanted” to cheaper cities, in order, I suppose, to separate the sediment.

Underneath it, “revitalised”, a word also used in the marketing for vaginal rejuvenation, and the phrase “vibrant neighbourhood”, meaning “still has enough poor people to feel like real life”, and “emerging” in the context of boroughs that middle-class people have recently colonised. There’s a sense you get, through these words that are hurled against building hoardings like leftover milkshakes, through the language peppered across property pages and estate agent ads, that the areas they talk about have just been discovered, dug up overnight by archeologists in Topman suits. That, until the Waitrose came, all this was just dust.

It’s easy to become obsessed with gentrification, living in a city, and it’s easy to be cynical. There’s long been a shortage of decent housing – one of the reasons it is only now being called a crisis is that today it affects the middle classes, too.

The aspirational hoardings on a building site I used to pass have recently come down – those photographs of dream girls laughing over brunch – to reveal the fact that, while developers have gutted the building, they have chosen to keep the façade, including the sign that says “Hospital for Children”. Why? Why remind the new residents, choking on their mortgages, that once babies died here? Because these aren’t just new-build flats, these are “carefully crafted apartments woven into the fabric of the original building”. They’ve used the boiled down stock of the place to retain the taste. In the same way that a fancy hotel in Soho has installed a red neon “peepshow” sign, the building’s value relies on memories of what stood before. A couple of years ago, alongside words like “innovation” and “fresh”, one London hoarding displayed the quote: “I like thinking big. If you’re going to be thinking anything, you might as well think big.” It was from Donald Trump.

The vagueness of the words on new buildings’ hoardings reflects the vagueness of the processes that got them built in the first place. Public consultations on redevelopment are famously opaque. A colleague told me about a public meeting for the regeneration of railway arches rented by market traders – the allocated two hours were dribbled away discussing whether the front shutters would open inwards or outwards, rather than whether the tenants would ever be able to return.

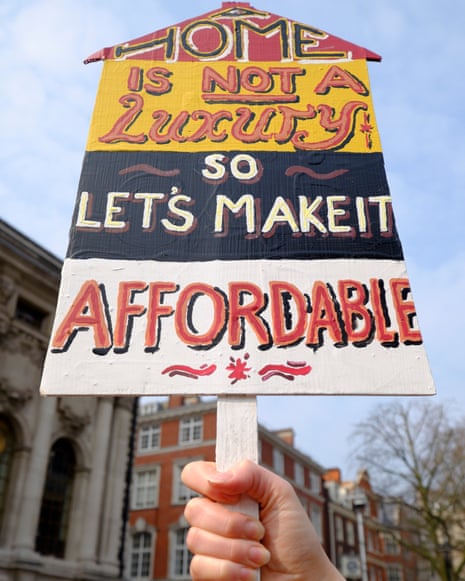

“Affordable” – that’s another one. The term was quietly broadened in the Housing and Planning Bill in January, with “starter homes” costing up to £450,000 – 17 times the average British salary. In the rental sector it means social housing providers must charge no more than 80% of market rent. In the language of gentrification, the word “affordable” has a very different meaning.

There is some poetry in this obscurity, of course, this language as delicate as clingfilm. I like to imagine the copywriting meetings happening at 4am in a smoky jazz club, free-associating advertisers applauding their use of vowels, going so deep into the etymology of a word that they come out the other side, enlightened. Better that than the suspicion that marketers are encouraged to deal in shadows, using the original meanings of words simply as scaffolding. The result being that councils, rather than having to improve cities, are allowed to sell them off square foot by square foot, displacing communities, but profiting from what the residents left behind.

“Poor doors”, “luxury”. Every day I add a new word. “Pioneers”, “authentic”. There are 50 words for the feeling you get when you wake up in a flat having dreamed of the ghosts that once lived there, and even more for the silent click of a new cutlery drawer. To live in cities today means we must all learn the language, and fast.

Email Eva at e.wiseman@observer.co.uk or follow her on Twitter @EvaWiseman