Visitors to the F54 Kiezladen (neighbourhood cooperative) in Berlin’s Neukölln district are hit by the smell of chopped onions. Inside the kitchen, members are busy chopping vegetables to make a supper of soljanka, a Russian soup, for the stream of residents arriving for a beer and a chat – and, in some cases, to see the rental rights lawyer who is volunteering advice this evening.

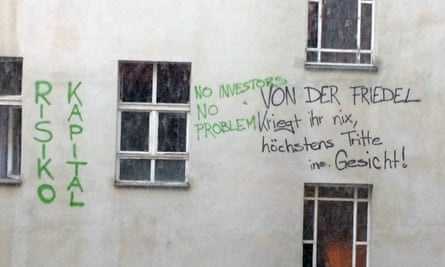

The cooperative – formally known as Friedel Strasse 54 – was recently given notice to quit by the investor that had bought the apartment block in July, Pinehill sarl: a mailbox company registered in Luxembourg. The septuagenarian dental technician who occupied the ground-floor workshop here for decades has already been evicted.

It is an increasingly common scenario in Neukölln, a sprawling neighbourhood that has become a magnet for young Europeans in recent years, and has found itself in the sights of international property developers as a result.

Matthias Sander (his requested pseudonym for talking to the Guardian), a 32-year-old history and politics teacher, is a resident of one of the 20 flats that make up F54. “The cooperative is basically a squat now; we’re just waiting to see what happens,” he says. “Our only hope is that our own initiative will kick in somehow, or the property market will collapse, allowing us to buy the building ourselves.”

Until a few years ago, investors discovering Berlin ignored Neukölln as too scruffy and working-class. It has the largest number of migrants of any district in the city, and the highest number of social welfare recipients. But in recent years, as Berlin’s housing market has boomed, investors have been seizing everything they can: “I’d say every second building has either been bought or is in the process of being bought,” Sander says.

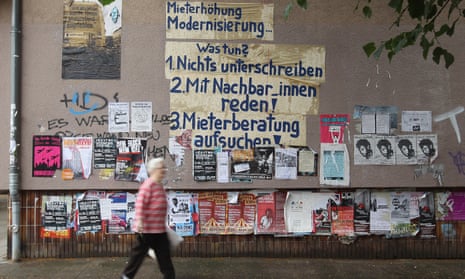

Recognising that the city’s Social Democrat government had minimal interest in bucking this trend (the mayor said she welcomed a middle-class influx), the Neukölln Tenants’ Alliance set about collecting signatures in support of introducing “milieuschutz” in the area. Under this law – translated as “social environment protection” – real estate is shielded against owners’ attempts to renovate and modernise it to the extent that existing residents could be forced out.

“The milieuschutz should ensure that neighbourhoods in Berlin remain lively and socially mixed, enabling anyone to live wherever he or she wants,” says Hans Panhoff, a city councillor responsible for building, planning and environment in the neighbouring district of Kreuzberg, which has borne the brunt of Berlin’s gentrification drive.

Panhoff says the law can work in conjunction with other measures, such as new rent control regulations and the right of authorities to block sales, should they be able to raise the money to buy a building themselves. (Currently, there are two prominent examples of tenement blocks in Kreuzberg-Friedrichshain whose residents would have faced eviction by the Luxembourg investor who was on the verge of snapping them up. Instead, the district authorities have provisionally secured both blocks under this “communal right of first refusal” rule – although Panhoff says the cases are in legal limbo, while experts agree this model will not offer a long-term sustainable solution due to a simple lack of funds.)

Panhoff’s department has produced a flyer to inform local residents of the city’s housing laws: “Many people are unaware about what they have to tolerate and what they don’t,” he says. “We’ve tried to increase awareness, and have seen a rise in the number of queries as a result.”

The milieuschutz laws are far from new – some German cities began implementing them more than 40 years ago – but their spread has never been as rapid as now: a time of unprecedented real estate price rises.

In areas protected by the law, owners are forbidden from changing floor plans, merging two flats into one or splitting large flats up into several, adding balconies or terraces larger than four square metres, installing fitted kitchens or undertaking luxury bathroom renovations – or using the flat as a holiday let.

“We have been seeing a rapid increase in such modifications being carried out,” says Andreas Haltermann of the Tenants’ Alliance, “primarily so landlords can increase the rent – sometimes to an extortionate level – with the intention of pushing existing residents out, so they can either sell the flat or rent it out at a much higher rate.”

Haltermann claims the milieuschutz – which was passed by the Neukölln government in its “most urgent” areas in the new year, and finally came into full force this summer – has already prevented planning permission on several building projects.

“We’re aware that property companies are capable of many tricks to get conversions through regardless,” he says, “but we have bureaucrats on our side who are at least going to make their lives as difficult as possible, and hopefully slow down the process so much that large investors are put off buying here.”

Martin, a 49-year-old arts promoter, is reluctant to give his full name because he is still in legal dispute with a Spanish businessman who recently bought the building in which he has lived with his wife for 12 years. Martin says the milieuschutz has so far ensured the string of modernisation measures the new owner wanted to carry out were not allowed to happen.

“He wanted to put in under-floor heating, to change the floor plans, to insulate the walls, to install solar panels – you name it,” he says. The measures would apparently have led to a more-than-threefold increase in his rent, from €600 to €2,000. “My wife and I both work, so we might have been able to afford it – but for our neighbour it would have meant paying 85% of her wages towards rent. She would have been forced out.”

Martin is relieved his neighbourhood building inspectorate warned the owner that the upcoming milieuschutz would mean he could not carry out the measures. “You feel safe and secure when it is your own local authority that steps in and says that for you, rather than you having to fight the fight yourself,” he adds, at the same time admitting the legal fight is far from over.

Of course, Germany is very much a renters’ market, with 85% of people renting and sympathy for property owners not typically uppermost. Rent rises are, in theory, capped – the longer someone has lived somewhere, the lower their rent is and the more rights they have.

But if the owner upgrades the property, he is able to offset a considerable chunk of those costs on to the rent. Long-term, sociologists warn, this is likely to water down the healthy social mix in neighbourhoods that city residents often cite as one of the reasons life in Berlin is so pleasant and relaxed.

‘I don’t want to go’

The milieuschutz has done little to help the residents of Lenaustrasse 23 and Hobrechtstrasse 62, known collectively as Lebrecht 2362, in Neukölln. On the day the Guardian visits, the new owner of the buildings, a Berlin developer, has sent his own inspector to compile an inventory of the 30-or-so apartments, ahead of a planned luxury upgrade.

Henry, a social worker, nervously shows the inspector around his quirkily decorated flat, painted in shades of green, turquoise and yellow and with a sign above the toilet which reads: ‘Free your mind and your arse will follow.’

“I’ve lived here for 21 years,” Henry says. “I’m quite happy with how it is. I don’t want to go, but I fear I might have to.”

Henry’s neighbour Simi, a cabaret artist who is here to give him moral support, says: “We need to fight for Berlin – for the fact this is a city where lots of different people from different walks of life can live under the same roof.”

Sven Theinert, a manager and spokesman for the renters who lives on the second floor, says: “We would like to have been able to rely on the milieuschutz, but the local authorities gave permission for these flats to be converted into owner-occupied flats before it could even kick in.

“As far as we’re concerned, the milieuschutz is toothless in the fight against the investors’ will as long as the politicians are not behind it. Look at the number of lifts that are being installed in 19th-century buildings across the district. That speaks volumes for just how effective it is.”

Theinert says the residents have tried talking to the new owners: “We’ve told them we’re ready to go along with the modernisation measures, that we’ll take rental rises on the chin within reason – but we just don’t want the luxury refit they’re planning.”

Criticism of the milieuschutz has also come from the home owners’ association Haus & Grund (House and Land), which has accused the authorities of “taking away from people the chance to buy, at a time when it has never been so easy to secure provision for old age due to the low borrowing costs”.

Meanwhile the Chamber of Industry and Commerce has described the measures as “a renewed attack on the ownership rights of property owners, which is having a detrimental effect on the investment climate in the city without doing anything to keep rents under control on a mid-term basis”.

Back at Friedel Strasse 54, Sander the teacher sits amid graffiti reading “We’re here to stay” and “No bling in the hood”. He demonstrates how the owners tried to prove the facade was damaged enough to merit an expensive and, according to him, superfluous energy-saving insulation procedure. “But this house has been standing since the 19th century, and its walls are 60 centimetres thick. It’s absurd.”

A court blocked the new owner’s attempts to prettify the courtyard with a new shed for the rubbish bins, and by insulating the walls. But Sander was forced to accept the installation of central heating in the flat he shares with his two children.

At least he managed to save from demolition the ceramic stove – which is as old as the flat itself, but which the investors wanted to tear out.

“Some might consider it old fashioned, but it’s part of the 19th-century allure of the place and produces a beautiful heat,” Sander says. “The fact I managed to persuade the court to let me keep it feels like a small victory at least – even while the bigger threat still looms.”

Are you experiencing or resisting gentrification in your city? Share your stories in the comments below, through our dedicated callout, or on Twitter using #GlobalGentrification

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion