Focus: San Diego’s unprecedented transportation goal

No U.S. city has quickly managed to get high numbers of residents to swap their cars for trains, buses, bikes and sidewalks

A cornerstone of San Diego’s widely lauded vision to wage war on climate change — getting people out of their cars and onto public transit, bicycles and sidewalks — has never been achieved by any metropolis in the United States on the scale and time frame called for by the city.

Leaders here seem unfazed, perhaps in part because they haven’t fully analyzed key data measuring the challenge ahead.

“It’s still very, very early in this process,” said Jack Straw, director of land-use and environmental policy for Mayor Kevin Faulconer. “We agree this is a very aggressive plan and it’s going to take a lot of work to achieve, but by no means do we think it’s impossible.”

Environmental groups that helped the city shape its blueprint against global warming couldn’t provide an example of a region that has pulled off what San Diego dreams of doing. Yet they remain hopeful that the vision is within grasp, and despite evidence to the contrary elsewhere across the nation, they believe tough action by elected officials to boost alternative forms of transportation will make the difference.

“I do not see us hitting the goals that the city committed to hitting” without ramped-up efforts, said Nicole Capretz, executive director of the San Diego-based nonprofit Climate Action Campaign. “At this point, there’s not sufficient political leadership.”

Transportation experts nationwide said that to realize small but consistent gains over many years, cities need to significantly expand mass-transit infrastructure, get businesses to subsidize employees who take the bus or train to work, create protected bike paths and make it painful for people to commute by minimizing parking lots and street parking.

In coming decades, San Diego’s Climate Action Plan calls for slashing the city’s greenhouse-gas emissions in half. The vision relies heavily on state and federal mandates designed to shrink emissions from California’s largest source — transportation. In fact, thanks to those regulations, the city will be able to meet the 2020 emissions benchmark set forth in its climate plan even if it fails to get any reductions from local efforts.

City officials stress that San Diego has committed to rolling out its own programs to curb emissions, most notably by moving toward a greener electrical grid and striving to greatly limit the number of vehicle trips within city boundaries.

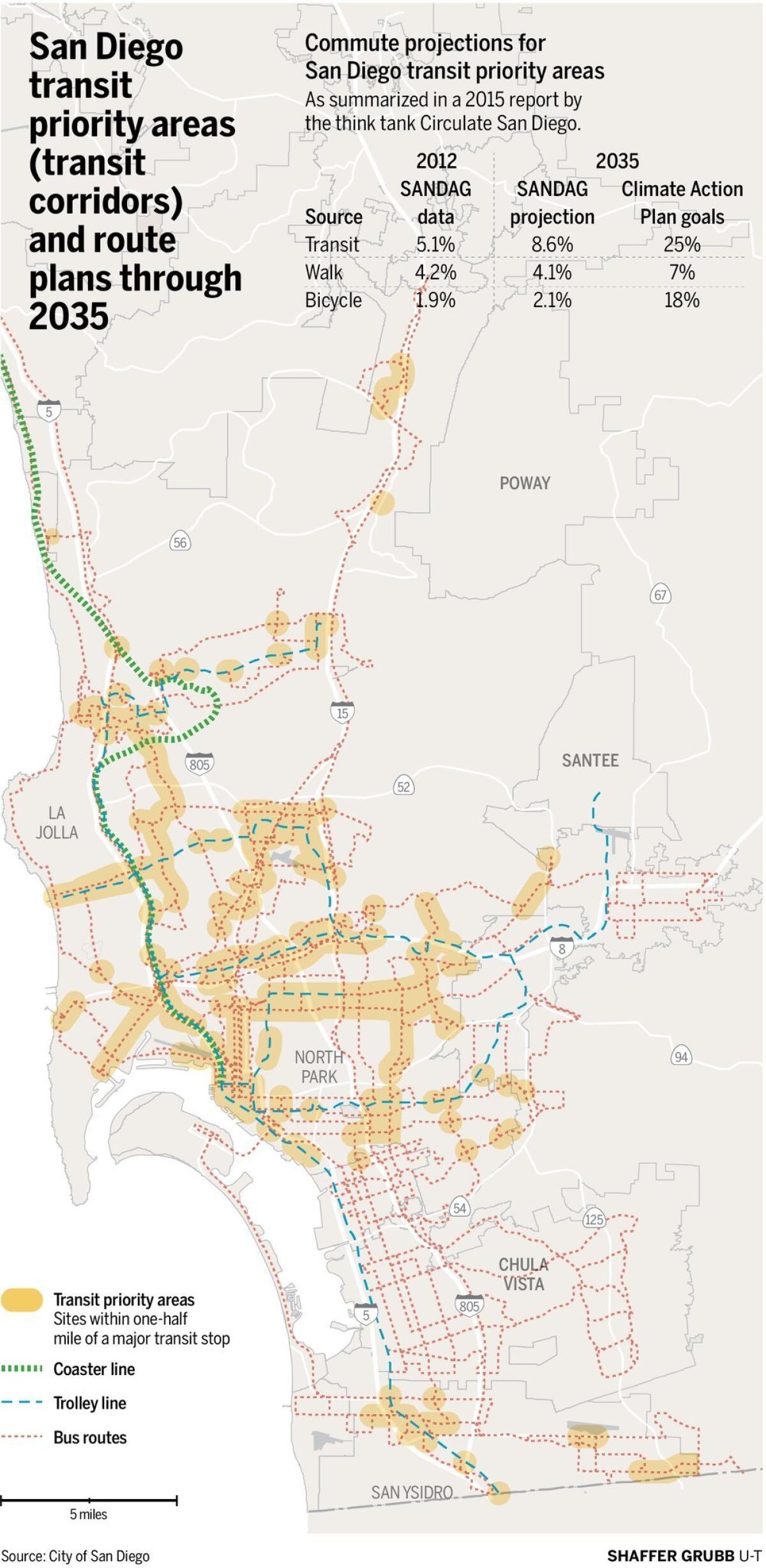

To reduce tailpipe emissions, the city’s climate plan calls for 22 percent of all commuters in transit corridors — those who live within a half-mile of a major transit stop — to bike, walk or take public transportation to work by 2020. The figure rises to a whopping 50 percent by 2035. That would represent more than 241,200 people of the city’s total workforce by that time.

At present, about 84 percent of residents citywide drive to work and about 8 percent take public transit, walk or bike, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Most of the remaining people work from home or commute by taxi.

FOR THE RECORD

An earlier version of this story didn't mention both authors of a 2015 report on alternative transportation methods in San Diego's transit corridors.

The city said it doesn’t know what percentage of residents in the transit corridors currently drive to work. Last fall, the transportation think tank Circulate San Diego and the Climate Action Campaign released a report that found about 11 percent of people in transit corridors biked, walk or used mass transit to get to and from work. That means the city would need a jump of 11 percentage points to meet its 2020 goal and almost 40 percentage points by 2035.

City officials said they hadn’t seen the data, which relied on statistics from the San Diego Association of Governments, the agency that coordinates the region’s transportation projects, such as trolley and bus lines.

The report also found that based on SANDAG’s current regional transportation funding plan, the city of San Diego would see single-digit increases in transit ridership and other alternative modes of transportation — far short of the goals in the Climate Action Plan.

By 2020, the city is projected to see 13.1 percent of commuters who live in transit areas take public transportation, bike or walk to work, and 14.8 percent by 2035, according to the Circulate San Diego report.

Unprecedented vision

Metropolitan regions frequently cited as having successfully transformed themselves into mass-transit capitals have made steady gains over decades. Even with widely lauded coordination among forceful lawmakers, enthusiastic businesses and impassioned activists, none of those sites came close to meeting San Diego’s targets.

For example, the city of Seattle, a national model for aggressively promoting alternative modes of transportation, saw a 6.6 percentage point increase in commuters using transit, walking or biking between 2000 and 2014, according to census data.

Arlington County, Va., often hailed for a longstanding policy of building high-density communities around transit lines, reported a 4.6 percentage point bump during the same 14 years.

And Berkeley, which has some of the most progressive environmental policies in the nation, experienced a rise of 7 percentage points in that period.

While San Diego’s goals focus on its transit corridors, any boost in mass-transit ridership and active transportation in those areas likely wouldn’t come close to offsetting the gulf between the city’s overall objectives and what other urban areas have been able to accomplish.

San Diego wouldn’t say how it arrived at the eye-popping transportation targets, and it’s unclear how serious the city is pursuing them.

With transit planning and funding largely in SANDAG’s hands, the city has only a few other tools to encourage people to get out of their cars, such as encouraging developers to build denser, more walkable communities.

City Hall said it will soon embark on an update of its transportation master plan to further this aim, and that it will answer many questions — including those related to transportation — in what’s intended to be the first in an annual series of reports detailing progress on the Climate Action Plan.

For months, Capretz and the Climate Action Campaign have been asking the city to measure how a series of zoning plan updates for neighborhoods surrounding downtown San Diego would help boost alternative transportation.

It wasn’t until this month, when the city’s Planning Commission demanded the transportation estimates for all neighborhood update plans, that city officials said they would start calculating the impact of those plans on transit ridership, biking and walking.

Neighborhood updates are being completed for San Ysidro, North Park, Golden Hill and Uptown (an area that includes Hillcrest, Mission Hills, Bankers Hill and University Heights). They could easily be in place for decades, based on past precedent.

The city said it will update the commission at its Oct. 6 meeting on efforts to analyze transit ridership for the San Ysidro plan update. It hasn’t said whether the full analysis will be completed before the plan update goes to the City Council for approval.

“If we’re not doing these community plan updates right, if we’re not doing any kind of analysis that demonstrates that this build-out will get us this [transportation] shift, then we are undermining and not being faithful to the goals of the” city’s larger pledge against climate change, Capretz said.

For the most part, the neighborhood land-use plans look fairly similar to what’s currently on the books. While the number of housing units allowed will increase slightly in North Park, San Ysidro and Golden Hill, the Uptown portion is actually slated to see a reduction.

City officials point out that existing zoning rules allow these neighborhoods to get significantly denser, and that the proposed updates, to an extent, promote a shift away from single-family homes in favor of mixed-use apartment complexes along transit corridors.

“In the end, what you want to ensure is that your community plan is balanced and most importantly that it’s achievable,” said Jeff Murphy, the city’s top planner. “You don’t want to necessarily put in high densities where it just could never be built.”

The city’s reluctance to aggressively push high density on communities has sat well with some neighborhoods like San Ysidro, where Michael Freedman, chairman of the planning group there, said he had been concerned residents would reject the proposed update.

“I expected people to come out of the woodwork and say they don’t like this or that, but that never happened,” he said. “It was very well accepted.”

At the same time, the city’s tempered approach has frustrated some in North Park who would like to see a bolder campaign to champion development that fosters mass transit and active transportation.

“I am concerned that we are missing an opportunity to encourage a brave, new multi-modal world by using conventional 1960s citywide land-use based zoning,” said Howard Blackson, a member of the North Park Planning Committee and urban designer.

Risks and benefits

There’s little doubt that ultra-dense development would be politically risky. Pushback from homeowners who fear more traffic and a shift in the character of their communities is well-documented.

Bill Fulton, the city planner whom Murphy succeeded, left the position to work for an urban research institute in Texas after residents rebelled against his plans to build denser neighborhoods around two new trolley stops between Old Town and La Jolla.

“This is all very politically difficult, and I think this is the number one reason we haven’t seem more progress,” said Jemilah Magnusson, communications manager at the Institute for Transportation & Development Policy in New York City. “Even if you do have a municipality that’s willing to take on that political risk, [one or two electoral terms are] often not enough to get these projects implemented and going.”

Cities such as New York and San Francisco have sizable parts of their population forgoing the car in favor of buses, subways and other rail systems — more than 50 percent in a number of places.

However, those trends stretch back to the 1940s, when public transit ridership was at an all-time high in the U.S., according to the American Public Transportation Association in Washington, D.C.

The challenge that cities like San Diego face today is how to re-engineer neighborhoods in and around urban centers that have been neglected during decades of sprawling, car-centric development, said Andy Kunz, president of the Transit Oriented Development Institute, also in D.C.

“Basically, we’re trying to get back to where we already were as a nation” decades ago, he said. “The places that are coming back the quickest are those historic cores, the ones that already had those small blocks with the mixed-use buildings. The dense historic fabric is now what’s turning out to be the most valuable places of all.”

A number of major cities, including D.C., have started to embrace dense, walkable development paired with expanded mass-transit systems. Some elected officials have even promoted controversial policies that discourage driving, such as making public parking more expensive or eliminating most of it.

The growing desire to live in walkable neighborhoods has led to rental premiums in places such as Seattle, Boston and San Diego, said Christopher Leinberger, chair of The George Washington University’s center for real estate and urban analysis.

“The market is flashing incredibly strong signals to build high-density, walkable, urban stuff,” he said. “There’s pent-up demand, and it’s not being satisfied anywhere near fast enough.”

During the past decade, national transit ridership has increased substantially while highway miles traveled has remained relatively flat despite a growing population, according to the American Public Transportation Association. In 2014, Americans rode public transit roughly 10.8 billion times, the highest annual trip count since 1956.

In Boston, New York City and Washington, D.C., more than 90 percent of new development between 2010 and 2015 was considered pedestrian-friendly, according to a study this year by Leinberger.

By comparison, of all new developments in the San Diego metropolitan region in the past five years, only about 23 percent earned the same designation.