In 2010, when the motorway between the German cities of Duisburg and Dortmund was closed as part of a cultural project, three million people walked, skated or cycled along the road. For one day only it had been transformed into a gigantic city boulevard.

Spatial planner Martin Tönnes took the opportunity to cycle from Essen to Dortmund. “There were so many people that, for the first time in my life, I experienced a bicycle traffic jam!” he recalls. “But that was when we started thinking about building a highway for bikes through the Ruhr Area. When we saw this mass of people cycling down the motorway, we understood there was a real demand.’’

Five years later, in December 2015, the first Radschnellweg (bicycle highway) in Germany was opened, between the western cities of Mülheim an der Ruhr and Essen. It is just the first stretch of what is going to be the biggest bicycle highway in the world: 62-miles long, connecting 10 cities and four universities.

When complete, the network will remove 50,000 cars from the road – with an associated annual reduction of 16,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions – according to the Regional Assocation Ruhr, where Tönnes is head of planning.

This new bicycle highway is very different from the narrow, painted strips which cyclists have to make do with in German cities, often risking collisions with motorised traffic. It is fully segregated from cars, a comfortable 13-ft wide, and equipped with flyovers and tunnels to avoid intersections (a footpath runs parallel to it). It is also fully lit, and will be cleared of snow in winter.

Together with the booming popularity of the electric bike, the highway could lead to a new era of cycle commuting in Germany. In the Ruhr, the distance between cities varies from six to 10 miles, which makes this industrial area ideal for commuting by bike, explains Tönnes.

“There are 1.6 million people living within 1.25 miles of the bicycle highway’s route; there are 150,000 students and 430,000 jobs. So I am not in the least worried about demand for it. The bicycle highway will persuade many people to start commuting by bike – with electric bikes making this choice even easier and faster.”

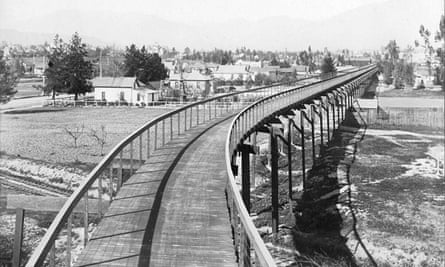

Bicycle highways are not a modern invention: the first was opened back in 1900 in California, with the opening stretch connecting the Green and the Raymond hotels, both in Pasadena. This segregated highway for cyclists was a wooden construction for which users paid a toll of 10 cents – but its success was short-lived. At the time, the number of cyclists was declining, and it was dismantled before the end of the decade.

When it comes building serious bicycle highways, the Danes and the Dutch were the great pioneers. While the Danish supercykelstiers are concentrated in and around Copenhagen, the Netherlands boasts a network of about 20 fietssnelwegen throughout the country.

The Netherlands started building bicycle highways in 2006 as a means to combat traffic jams. The first stretches were situated alongside busy motorways to offer frustrated motorists a visible alternative.

“The term ‘bicycle highway’ sounds very luxurious, so we prefer to talk of ‘fast cycle connections’,” says Ineke Spapé, a Dutch traffic planner and bicycle professor at Breda University of Applied Sciences. “In the Netherlands, they are not always 13-ft wide with expensive overpasses and underpasses. Sometimes there’s no space; sometimes it’s more practical to just improve existing cycle paths and connections. And it’s cheaper to give cyclists priority at a crossing than to build a flyover or a tunnel.”

Spapé is often consulted by traffic planners from other European countries, and her message is always: don’t spend too much time on feasibility studies and don’t aim for perfection. “For example, the Germans have guidelines that require footpaths parallel to their bicycle highways. When this is not possible, don’t cancel the plan: be pragmatic. What you want is to get people on their bikes – because the bike really is the future.’’

Many big German cities such as Frankfurt, Hamburg, Berlin, Munich and Nuremberg share this view, and are now studying the possibilities for Radschnellwege to suburbs and surrounding cities.

“Our population is growing fast, and that means traffic will increase and public transport will be under pressure,” says Birgit Kastrup from the Planning Association of Greater Munich. “We have to think of intelligent solutions for these problems.”

Munich is now considering to build a cycle highway to its northern suburbs of Garching and Unterschleissheim. “We believe the bike is the answer to traffic and environmental problems,” Kastrup says. “Bicycle highways are also a way to promote a healthier lifestyle.”

There remains one problem to be solved: finance. Cycle highways are not cheap, the costs vary between €500,000 and €2m per kilometre (£400,000 to £1.7m). In total, the Ruhr bicycle highway is predicted to cost €183.7m.

Whereas the Dutch central government subsidises the building of its bicycle highways, in Germany bicycle infrastructure is solely the responsibility of municipal and federal governments. The German minister of transport, Alexander Donbrindt, has made it clear that cities eager to build bicycle highways should expect nothing from him.

“He has been much criticised for a lack of vision,” Tönnes says. “Luckily, our federal government [of Northrhine-Westfalia] understands the importance of bicycle highways, and is changing the law to be able to finance the entire project.”

Other federal states are not so generous, which means cities such as Munich are still groping in the dark when it comes to financing their first project. “It will be exciting to see what comes out of this discussion,” Kastrup says. “But the political will is certainly there, so I am sure we will find the means.”

In Berlin, a city that struggles with huge debt, the idea was put forward to finance bicycle highways through advertising along the route. The proposal is in stark contrast to the Norwegian government’s recently announced plan to invest £700m in bicycle highways in and around nine of its biggest cities. The “super-sykkelveier” are considered an important means to combat CO2 emissions – a remarkable step for a mountainous country where winters are long and very cold, and cycling not as common as in other Scandinavian states.

Meanwhile, the Netherlands is working on 30 new projects, including an 18-mile bicycle highway to connect the northern cities of Assen and Groningen. And for the initiator of this project, a bicycle highway alone is not enough: “We want to offer an exceptional experience to the people who’re going to use the highway,’’ says politician Henk Brink.

Five different bureaus have been asked to come up with innovative ideas. There are plans for artworks along the highway that change with the weather conditions, and for a multifunctional highway where people can practise all kinds of sports when the rush hour is done – not to mention a highway with Wi-Fi hotspots and the possibility to charge your electric bike along the way. There’s also a plan for a canopied highway to keep cyclists out of the rain – or one that shelters cyclists from crosswinds by screens that rotate with the wind direction.

“These are just ideas, we don’t know what were are going to decide eventually,” Brink says. “But we believe that if you want people to start commuting by bike, you have to make sure they are going to enjoy it.’’

Asked whether Europe is entering a new age of long-distance cycle commuting, Spapé says: “Of course! The Dutch already have, thanks to the enormous popularity of electric bikes and our network of fast cycle connections. And in Germany it’s going to happen in the very near future.’’

According to Spapé, fast electric bikes enable commuters to easily cover stretches of 12 to 18 miles – provided there’s a well-designed highway with a smooth surface. “I have a colleague who commutes by power bike from Tilburg to Breda. That’s 16 miles,” she says. “In the future, more and more commuters will cycle – smiling – past the traffic jams.”

- This article was updated on 3 July to state that, when complete, the network will induce an annual, rather than a daily, reduction of 16,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook and join the discussion

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion