You see it in hospitals and offices, airports and schools. It is the go-to architectural language for service stations and retail parks, data centres and storage sheds. The ubiquitous acreage of grey cladding panels, offset with struts and wires and pointless bits of rigging, windows enlivened with grids of louvres, rooftops adorned with inflatable pillows. If you’re lucky, you might even get a swooping tensile canopy strapped on to the entrance, bringing a touch of yachty glamour to the grim shed beyond.

The scourge of our cities and out-of-town centres, this wretched language of Portakabin-moderne has become the default setting for countless developers and local authorities, bereft of budget and ambition. With its modular, prefab look, it bestows buildings with the deceptive impression of temporariness, masking the sorry truth that these flimsy boxes will long outstay their welcome.

So it might come as some surprise that this dreary style has a noble ancestry. It was invented by a group of men who are now Lords and Knights, as a BBC series starting this week seeks to tell us in lavish detail. Accompanied by an exhibition of the same name at the Royal Institute of British Architects, the Brits Who Built the Modern World is a celebration of the influence of Norman Foster, Richard Rogers, Nicholas Grimshaw, Terry Farrell and Michael Hopkins – and his wife Patti, who has for too long been written out of the history of the famous five.

It reminds us that this world of curtain walls and clip-on facades was once brave, modern, and even shocking. It was the product of children who had grown up with Meccano and moon landings, their thirst for the future fed by the storyboards of Eagle comic and the thrill of the Festival of Britain. Together they would dream up a brave new world that would be modular and mechanised, an architecture that came in a flatpack box and smelt of engine oil. And they wore some pretty wild outfits too.

It was a style that fetishised the imagery of technology, that elevated catalogue components of spigots and sprockets, gaskets and rivets, into the canon of the architectural orders – and so it became known as High Tech. It spoke of efficiency and lightness and factory production, even when it ended up producing some of the most bespoke and expensive-to-make buildings in the world. At its best, it produced buildings of extraordinary energy and excitement – from the Pompidou to Lloyds – but its imitators have left our cities strewn with dumb boxes, clumsy lumps that have forgotten what it is to compose a facade and make a street.

But this is not the whole story. What the Brits extravaganza fails to mention is that this generation of British architects, born in the 1930s, were not all Haynes manual obsessives and production-line worshippers. So below we bring you an alternative, not-so-famous five Brits who also helped to build the modern world.

Neave Brown

While the Lords of High Tech might espouse social values, few have turned their attention to the challenge of social housing – unlike Neave Brown, an adoptive Brit, born and educated in the US, who made it his life’s work. Employed by the London Borough of Camden’s architects department during its most progressive era, from the mid-60s to the end of the 70s, he designed two of the finest council housing schemes of the period – the Fleet Road flats (where he now lives) in 1967 and Alexandra Road, from 1968–78. A bold reinvention of the London terrace, Alexandra Road looks like something conjured by the Mayans, a ziggurat of stacked houses and maisonettes that curves along the edge of a railway line, extending great concrete fins down to a street to define private gardens and terraces. For all its formal ingenuity, it was part of Brown’s ambition to “return to housing the traditional quality of continuous background stuff, anonymous, cellular, repetitive, that has always been its virtue.”

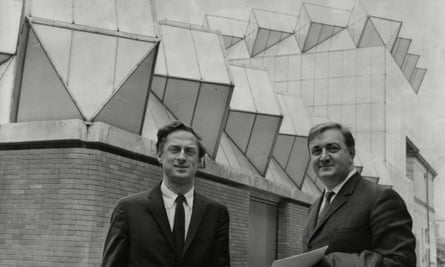

James Gowan

Tutor to Richard Rogers and unsung partner of the rambunctious James Stirling, James Gowan was key to Big Jim’s early work – when the practice was established as Stirling and Gowan – including the seminal Department of Engineering at the University of Leicester, completed in 1963, which would define Stirling’s style for the following decades. Considered to be the first postmodern building in the UK, it channels an eclectic range of references and delights in structural feats – from the angled wedges of raked lecture theatres that project out from a terracotta tower like strange concrete growths, to the saw-tooth roof of glass Toblerones that oversails the laboratories and workshops. Gowan always espoused using “the style for the job”, and split with Stirling over the Cambridge University History Library, which he felt merely recycled Leicester’s aesthetics.

Kate Macintosh

Having worked on the National Theatre for Denys Lasdun, Kate Macintosh joined Southwark Council in 1965, where she designed Dawson Heights, a little-known estate in East Dulwich that stands on its hillside site like a spectacular cluster of Tetris blocks. Conceived as a pair of mirrored, staggered ziggurats, the blocks follow the contours of the hill to wrap around a central garden, their multiple unit types interlocked in a dynamic spatial puzzle. Macintosh moved to work at Lambeth council, where she designed an equally inventive complex of old people’s housing on Leigham Court Road, arranged as clusters of two and three-storey blocks. She was highly critical of the anonymity of extruded housing of slabs or point blocks that was favoured by most local authorities at the time, arguing that “housing design is the balance between the expression of the individual dwelling and the cohesion and integration of the entire group.”

Ted Cullinan

Of his generation, Ted Cullinan is perhaps the most far removed from the technocratic world of Milords Foster and Rogers, his buildings having more in common with something you might come across in the Hobbits’ Shire than the factory floor. Educated at Berkeley, California, he brought back a laid-back west-coast view of the world, and set out to design with the philosophy of “long-life, loose fit, low energy” – with the idea that buildings should be worn by their users like a favourite cosy cardigan or pair of baggy jeans. His Downland Gridshell, nominated for the Stirling prize in 2002, looks like a bulbous carapace discarded by some great worm, while the Teletubbies would be at home on the grassy rooftops of his Cambridge Centre for Mathematical Sciences.

Christopher Woodward

Working for arch-brutalists Alison and Peter Smithson from 1963–71, Christopher Woodward was instrumental in the design of the now-listed Economist Plaza and the Robin Hood Gardens estate in East London – which has sadly suffered a stickier fate. Currently subject to demolition, to be replaced by a generic blandscape of higher-density developer housing, it is an ingenious complex of streets in the sky, cleverly arranged in section, but built of slender pre-cast concrete panels that were never up to the job and have since crumbled. Woodward went on to work with Derek Walker on the Milton Keynes shopping centre, a 650-metre long white steel and mirror-glass temple to shopping that applied the precision of Mies to a sprawling retail shed.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion