Playgrounds for All

The success of “joint use” programs in San Francisco and New York shows the benefits of opening schoolyards up to the local community.

On a crisp, sunny Saturday morning in February, the yard surrounding San Francisco’s Alvarado Elementary School buzzes with activity. Adept climbers grunt as they swing along three sets of monkey bars, scooters zip across the blacktop, and basketballs bounce alongside playful jibes between parents and children. Over it all, a toddler’s jubilant squeal rings out. Ten years ago silence and stillness would have reigned on the weekend, the gates of the chain-link fence locked.

The need for open space can be dire in dense urban environments, especially amid an epidemic of obesity. According to a 2013 report by the nonprofit NYC Global Partners, in 2007 2.5 million New Yorkers lived farther than a 10-minute walk to a park. Meanwhile, “most schoolyards were locked to the surrounding community all summer, every weekend, and every evening.” In many places, they still are.

When San Franciscan Mark Farrell sought a flat, car-free space to teach his children how to ride their bikes in June 2011, he recalled fond memories of using the local schoolyard with his father. But when Farrell and his own kids arrived, they found it closed. The story might have ended there—but he happens to be a member of the City’s Board of Supervisors.

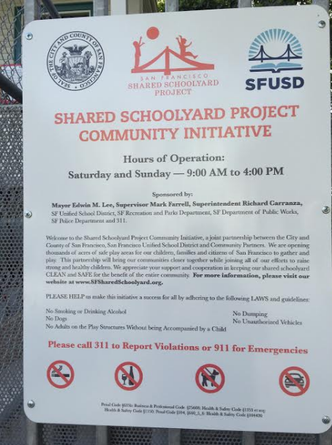

Farrell investigated and found an unfunded pilot program to reopen schoolyards, created under then-mayor Gavin Newsom’s leadership in 2007, largely sitting dormant. Farrell took matters into his own hands, and this year the Shared Schoolyard Project will expand to 80 schools, opening each space from 9 to 4 on Saturdays and Sundays, often after the fanfare of a ribbon-cutting ceremony.

Some were concerned that opening the playgrounds would make them vulnerable to destruction. But a stolen trash can and a broken terracotta pot are the program’s worst reported incidents. Vandalism and trespassing have even decreased. Why? “An active schoolyard is a safe schoolyard,” Farrell says. Weekend users seem to feel a sense of stewardship, picking up granola bar wrappers, broken pencils, and other school-day detritus. The feeling is mutual. Participating schools aren’t required to open their bathrooms, but Alvarado’s principal Jennifer Kuhr Butterfoss does anyway: “I know what it’s like to be a mom at a playground with a kid who has to go.”

Use of the space for weekend events—like Argonne Elementary’s Spring Fair complete with food trucks, carnival games, rock climbing, and live animals as well as smaller gatherings like the community fundraiser organized for a bereaved family at Monroe Elementary—further increase local businesses’ engagement with the schools, and taxpayer goodwill.

Opening existing playgrounds to the public is such a clear win-win that it seems like an easy solution to cities’ lack of open spaces. It isn’t.

“For more than 200 years, U.S. schools have provided local communities with public assembly spaces as well as space for community programs,” explains a 2008 joint report by UC Berkeley and the Oakland nonprofit ChangeLab Solutions. The concept, known to policy wonks as “joint use,” generates perennial debate in education and urban-planning circles. “School facilities are natural sites for shared use [because they] already have certain features ... such as fences separating fields from busy streets and handicap accessible ramps,” adds a report out of Harvard Law. Yet stumbling blocks to open access abound.

Los Angeles Unified School District’s chief facilities executive, Mark Hovatter, says access to the city’s playgrounds and sports fields isn’t “like it was when I was a kid and you could just walk in and use them on the weekend.” Today, he explains, the district requires permit applications for short-term use and longer arrangements governed by joint-use agreements with individual private groups, like club soccer teams. LAUSD currently allows open access to some fields, but increased wear on synthetic turf means it needs to be replaced more frequently, and adds up to millions of dollars.

Hovatter says state legislation allows the district to charge communities for use of the fields, but that would mean “rich kids would continue to have access, while the ones who need a free place to play the most would not.” But LAUSD can’t just keep bearing the costs, he says. “We have to balance the need for open space against our primary mission to educate kids. We can’t let our desire to prevent unfairness turn us into a parks-and-rec department instead of a school district.”

San Francisco surmounted this obstacle by rallying its municipal agencies to work together. Under the pilot program, each city department was expected to simply absorb the cost of participation. Unsurprisingly, only one schoolyard in each of the 11 supervisorial districts opened under this model. Then Farrell came along and jump-started the effort with private fundraising plus involvement of the nonprofit San Francisco Parks Alliance.

An operating budget of $300,000 a year pays for SF Recreation and Parks patrol officers to open and close participating schoolyards, and inspect them each afternoon to see whether SF Public Works needs to jump in for priority cleanup, repairs, or graffiti abatement. SFPD officers check in throughout the day. Participating schools receive two annual amounts: a $1,000 no-strings-attached stipend for the PTA, and a $2,500 activity fund for weekend events “that promote and bring together the neighborhood community.”

Still only 30 of 106 schools in the district volunteered to take part. About 25 aren’t eligible for various reasons—the playground for Tenderloin Community School, for example, sits on the building’s roof. The remaining 50 schools opening their yards this year do so at the behest of the SFUSD Superintendent, Richard Carranza. The president of the Board of Education, Matt Haney, explains, “Once we saw how well it worked, we knew we had to make it a priority to open as many of our schoolyards to the public as possible, whatever that takes.”

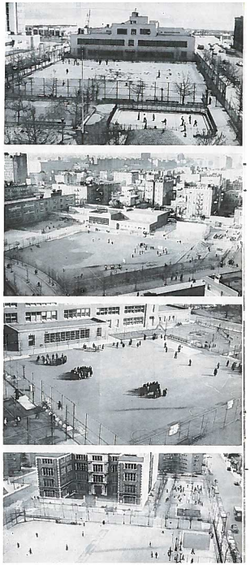

San Francisco’s joint-use program is modest in comparison with New York’s. Dubbing schoolyards an “underutilized resource” in 2007, Mayor Bloomberg made good on an Earth Day speech promise and launched the Schoolyards to Playgrounds Initiative, allocating more than $100 million in funding. The program immediately opened 69 schoolyards—from school close until dusk Monday through Friday, and from 8 to dusk on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays—by reimbursing each school custodian up to $50,000 a year for associated labor and maintenance.

Though the City reduced capital funding in 2009 and 2011, the remaining money—and private matching dollars provided by one nonprofit, Trust for Public Land, as well as help from another, Out2Play—funded renovation of 160 more schoolyards across all five boroughs with investments in play structures, sports equipment, trees, benches, fencing, turf, landscaping, and the sealing and painting of surfaces. In at least one case this meant transforming a parking lot into an oasis of color and movement.

First Deputy Commissioner Liam Kavanagh says NYC Parks identified candidates by looking for neighborhoods with high population density (or a population projected to grow), limited existing play space, and a lack of vacant land for development. Since the Department of Education was reluctant to give up control of its property, Kavanagh reports, the city agreed to handle procurement and construction, partnering with schools and communities in the design process, and then to turn the completed sites back over to DOE to maintain and operate.

It isn’t the first time NYC Parks and DOE have formed a tag team. In 1938, the renowned city planner Robert Moses—dubbed a visionary by some and reviled by others—began the Jointly Operated Playgrounds program. “As the city was growing and developing new neighborhoods, they decided to set aside adjacent land for parks and playgrounds whenever they built a new school,” says Kavanagh. To this day, 265 playgrounds next to schools are owned by DOE but operated and maintained by NYC Parks. The specifics vary by site, but they are all open to the public, sometimes even during the school day.

If San Francisco’s experience proves the feasibility and benefits of increasing use of existing public resources, New York’s makes a larger point: The more people who will ultimately utilize a space, the higher the likelihood of both civic and private investment in it.

In response to the crisis in education funding created by California’s Proposition 13, many school districts sold off property. A high school in East Palo Alto, for example, was demolished and replaced by a Home Depot. Cutting costs and liquidating assets is a common impulse when faced with budget shortages. The successful joint-use programs for the schoolyards of San Francisco and New York, however, show that our public entities may be better off doubling down, increasing and diversifying use of their facilities.