My attire this morning: long johns under jeans, two layers of wool socks, heavy hiking boots, a turtleneck, two scarves, gloves, a fleece, a down parka and a knitted hat. I'm in the most populous city in the country, it's the coldest day of the year, and we're off to track coyotes.

When I lived in the mountains of North Carolina, I never thought I'd end up hunting coyotes in New York City— maybe a rat or a pigeon. But coyotes, which have always been smart, are finally getting street-smart. They've been spotted around town, and chances are, they're going to stay.

All over North America, as their populations expand, coyotes have been on the move—from forests to suburbs to cities—looking for places free of predators and hunters to call home. Coyotes roam most during January's breeding season, and by March they'll have found their dens. In the city, this could be anywhere—a trash dump, a vacant lot, an overgrown corner. Coyotes in Chicago built a den on the top floor of a parking garage. The only evidence of dens in New York so far is in the Bronx and wooded parts of the parks. In March, a coyote was spotted on the roof of a bar in Long Island City, Queens.

The sightings started in late December 2014. About two weeks later, the New York Police Department (NYPD) found the city's first official coyote (whom they named Riva) in a Riverside Park basketball court on 72nd Street in Manhattan. After someone called to report a coyote roaming the area, the NYPD used two tranquilizer darts to sedate and capture her. That was around 10:30 p.m. on January 10. Two weeks later, Stella appeared.

Stella stalked the streets near the Con Ed plant on the East Side of Manhattan before police wrangled her in nearby Stuyvesant Town, a massive condo complex. The NYPD captured her as they would a delinquent dog: They roped her neck, sedated her, placed her in a carrier and transported her to Animal Care and Control of NYC. After determining that both females were healthy, they released them in the Bronx, where coyotes have been living and breeding for 20 years.

Because there are fewer predatory threats and more food, coyotes have begun to flourish in the suburbs, like those around Chicago and parts of the Bronx and Westchester County, New York. In April 2015, there were two instances when coyotes attacked men in Bergen County, New Jersey, across the Hudson from Manhattan. (In the first case, the animal was found to be rabid; the second is still at large.)

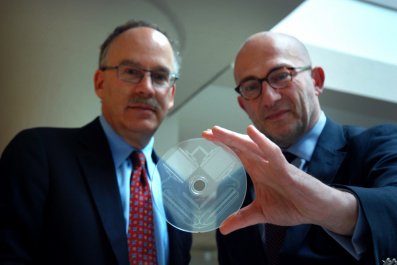

But the suburbs are becoming overcrowded. Because coyotes are territorial, and only one pair will mate in any given territory, coyotes are venturing ever farther to mate and establish homes. "They're New York's newest immigrants," says Chris Nagy, director of Research and Land Management at Mianus River Gorge in Bedford, New York. "They're just looking to make a living just like anyone else." Since 2006, Nagy and Mark Weckel, a conservation biologist at the American Museum of Natural History, have been working with high school interns to photograph coyotes in and around the city in a research program called the Gotham Coyote Project.

In the past two decades, coyotes have colonized Washington, D.C.; Tucson, Arizona; Los Angeles; Chicago; and Calgary, Canada. They've already been sighted in all of New York City's five boroughs. Strangely, though, they don't seem to like Long Island—it's the only landmass in the continental U.S. without a known coyote population. Experts from around the country, including Nagy, think it won't be long until coyotes settle down there too.

"Coyotes can get to Long Island the same way humans get to it: via the intricate network of bridges, tunnels and rail lines," says Javier Monzón, an ecologist and evolutionary biologist at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. Coyotes can also swim.

As a human, I need to rely on public transportation. I take two trains and a bus to get to Alley Pond Environmental Center on the border of Queens and Long Island, where I meet Nagy by his Subaru in the icy parking lot out front. He's with Erin McKenna, a 16-year-old high school intern, and together they're going to set up three motion-sensor cameras that will be tied to a tree. Nagy decided to stake out this park because he's just gotten word of a coyote near the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge in Queens and thinks this park is the next frontier.

Setting up a camera in the city means finding the "magic tree," says Nagy. Because humans and coyotes use the same paths, "it's a balancing act between the hidden and the not hidden." The key is to catch the coyotes, avoid the humans. "They steal SD cards," says McKenna, already attuned to the threats of a scientist's main predator: the loss of important data.

We move along the path, stuck between a highway and a wetland, with very few trees. Nagy ventures off the path, where the absence of footprints means the absence of people. He finds a tree with a trunk thick enough that the camera won't slip off and, with McKenna's help, attaches the camera to a rope and wraps it tightly around the tree.

"OK. Now do your thing," he says to McKenna, who gets down on all fours, stretches one arm out in an arch and gently places her bare palm down into the snow. She moves her other arm, then her back legs forward, one at a time. She giggles, yet her eyes are fixed and focused. Her coyote walk is calculated and convincing, and every half-second a red light on the camera indicates a closing shutter. Ideally, the real coyote will trigger the sensor in exactly the same way.

Nagy looks at McKenna's red gloves lying in the snow and tells her to put them on. "If you die out here, that's a lot of paperwork," he says. Next, he pulls out some Tupperware containing the lure—a cakey, white wafer that looks like an oversized Tums and smells like rotting cheese. He offers his gloves to Erin to save her own from absorbing the potent stench as she sets the lure. Erin carefully rubs the white disc against one branch, then another. She digs a delicate hole in the ground, drops the disc in, covers it in snow and pats it down. Nagy is less careful. He shoves his boot down to furrow the snow, drops in a disc, kicks more snow over it and packs it all down with one swift stomp. He says city coyotes are less suspicious than their country cousins.

Monzón concurs, saying it takes a few generations for coyotes to become "street-smart." Eventually, they'll "learn how to cope with the stresses of urban living," he says. They figure out how avoid humans and moving cars, and they travel at night. But most coyotes found in the city are young transients that move around recklessly, making them more vulnerable to the dangers of travel. Transients must learn the streets quickly. Those who don't can end up as roadkill, or caught.

Stanley Gehrt, an associate professor and wildlife extension specialist at Ohio State University, has been studying coyotes in the Chicago area since the '90s. He says researchers still don't know much about coyote family life. Whether they're pushed out of their childhood territories or venture out on their own is still a mystery.

Coyotes are sort of the millennials of the wildlife set, in that they're highly adaptive generalists who appeared in the late '80s. They both tend toward cities: humans for the culture, coyotes because, with no predators, it's a relatively safe place to be. In 2013, at the request of individuals and unnamed agencies, Wildlife Services killed over 75,000 coyotes in at least 44 states. A representative from the program, which is part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, says the goal was to decrease potential threats: to humans, livestock and agriculture.

Nagy tells me farmers don't want coyotes. And Gehrt says the same about ranchers. But despite the fears of these animal rearers, the preferred food of coyotes is small rodents, not livestock—another reason they do just fine in suburban and urban environments.

And once they move into the city, they stay. Three years ago, Gehrt's population estimate was 2,000 in Cook County, which includes Chicago's urban center and surrounding suburbs. He estimates that number has likely doubled today. In the surrounding suburbs, he finds six or seven coyotes every square mile, and that does not include pups. Within the busy urban center, Gehrt finds only one or two every square mile, which is similar to the low numbers he'd expect to find in a rural environment. "What I've learned is to never underestimate these guys," says Gehrt. "[Coyotes] are extremely opportunistic and don't always follow the same rules to hide from people."

Paul Krausman, a wildlife conservationist at the University of Montana, says that when he was studying coyote expansion into Tucson, he found animals haunting golf courses and cemeteries. "When the next bomb goes off," he says, "we're going to have cockroaches, scorpions and coyotes."

In New York, the coyote population may be on the verge of an explosion. Pups are born in April and May, and by the beginning of summer they're leaving the den. In July, young coyotes are running around parks. Nagy will be there to take their pictures—this time with the help of dozens of interns and, if he is successful, a scat dog trained to sniff out poop. With 50 samples already in the freezer, Nagy and Weckel hope to learn more about single coyotes: who they are, where they roam and what they eat.

"In the NYC metro area, they will become and are part of the biodiversity," Weckel says. "The question is, How will we learn to live with them?"