One September day in 2005, the Danish artist Olafur Eliasson set up a few tables in a bustling downtown square in Tirana and unloaded three tonnes of Lego bricks. The Copenhagen-born, Berlin-based artist, known for his enormous, immersive installations – he once installed a gigantic, glowing sun at Tate Modern – included simple instructions: residents of the crumbling Albanian capital, which was recovering from the end of communist rule in 1990, were to construct their visions for the city’s future out of Lego. “Building a stable society,” Eliasson said, “is only possible with the involvement and co-operation of each individual.” As the days passed, everyone from kids to adults, passers-by to committed users, gradually turned the plastic rubble into a glistening white Lego metropolis.

Part art installation, part crowdsourced sculpture, part urban intervention, the success of the Collectivity Project was a sign, perhaps, of our desire to become more involved in imagining the possibilities for our cities, even if our bricks-and-plastic creations will eventually be taken apart and packed up in a box. But it also signals the Lego Group’s desire for its products to be thought of as more than a child’s building blocks. In little more than a decade, the Danish company has gone from a $300m loss to overtake Mattel, the makers of Barbie, as the world’s largest toy-maker. It has achieved this through a canny mixture of movie franchising (The Hobbit, Star Wars, Harry Potter and, of course, The Lego Movie), an ever-expanding universe of video games (including Lego City for Nintendo) and even a forthcoming CBeebies TV show in 2016 based on its long-running Lego City line – featuring sets such as Lego City Museum Break-In and Lego City Prisoner Transport.

But Lego has also made an effort for the bricks to travel from the playroom to the boardroom, with the company appealing to artists, architects and other creative professionals to use their product as the building blocks for innovation. The Lego City video game may be just that, a game; but the company also donated 1m bricks to Dutch architect Winy Maas, who created 676 scale-model skyscrapers for the 2012 Venice Biennale. (They also gave Eliasson those three tonnes of bricks.) This October, the Lego Group held a workshop in Copenhagen, ahead of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, that tasked close to 700 children with building ideas for a sustainable future out of their products. Then there’s the recently released Lego Architecture Studio, a £149 instruction-free kit of white blocks that lets AFOLs (adult fans of Lego) play Frank Gehry and create their own architectural masterpieces. Lego even sponsors an urban planning project at MIT in the hopes that city planners, like architects before them, might use the bricks as tools to solve issues such as transportation and walkability.

It’s at this point that one could be forgiven for raising an eyebrow. Urban areas are bigger, denser, more complex and more reliant on technology than ever before. Can this most analogue of toys – dreamed up by an entrepreneurial carpenter in Billund in 1932 – really teach us how to build better cities? Or is this just a smart extension of the Lego brand, to persuade well-heeled parents that an expensive Lego City Monster Truck is a serious educational toy? Surely urban planners themselves, laden with degrees and sophisticated insights into the ebb and flow of urban life, aren’t actually plotting our cities using Lego City Train Station?

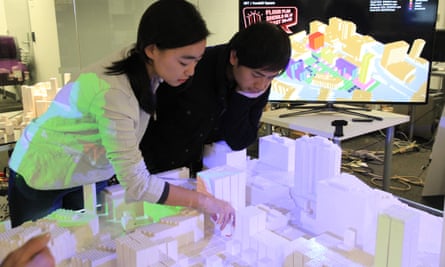

The answer might be found in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where MIT’s CityScope has created what managing director Ryan Chin calls an “urban observatory”. It’s a 30x60in Lego model of the city’s Kendall Square, on to which research scientists project digital data. For example, geolocated Twitter feeds from people working and studying in the real Kendall Square are mapped on to buildings; traffic information is projected on the brick roads. The idea, explains Chin, is to get a sense of how people live and work in the city. “We can look at flows of traffic, goods and people, and flows of energy,” he says. “What are the passive solar gains on a building? What are the shadows cast from a building on to a roadway?” Details about household sizes, population numbers and walkability can be programmed to provide, as he puts it, “a finely grained geospatial view of where things are happening in cities”.

In fact, software like this already exists: Autodesk or Esri CityEngine allow planners to map all kinds of data on to virtual 3D models of buildings and cities. Urban areas are intricate, shapeshifting ecosystems that presumably can’t be clicked together in an afternoon. Common sense suggests that a plastic city is too pixellated and limited to help planners design resilient cities that can adapt to climate change or find solutions to demographic changes and land use.

Chin argues, however, that it is precisely a lack of refinement that makes Lego useful as a design tool. He’s a fan of the malleability, interactivity and three-dimensional properties of the Lego model at CityScope. A former architect who has worked in automobile design, Chin sees flaws in traditional photorealistic renderings, which are often “Photoshopped to death”, he says. “You can hire the best photographer to make a house look beautiful, and you can hire the best 3D-renderers to make a model look beautiful.”

Lego, on the other hand, he describes as “pre-architecture”. The featureless bricks represent a city in progress, rather than a finished metropolis. By relocating a Lego office tower a few streets over or, say, widening a Lego road, they can instantly test the consequences of planning ideas. The addition of a sports stadium may affect the location of a bus stop or subway station; moving building X in front of building Y may disrupt traffic. Virtual reality technology such as Google Glass offers visualisations but not the same group interactivity, he says. And while 3D printing, touted as the future of design, could eventually offer both the interactivity and benefits of rapid prototyping, it is still out of reach: a resin maquette of San Francisco made earlier this year took two months to construct, cost $20,000 and you can’t move the Golden Gate Bridge.

But outside the lab, are any urban planners actually sitting around their offices with piles of blocks? Just as it is hard to imagine Zaha Hadid whipping out a Lego set when dreaming up her Dongdaemun Design Plaza for Seoul, it’s difficult to picture planners in London or Paris or Tokyo sitting crosslegged on the floor, mapping out a new business district from plastic plates, tiles and minifigs. This is where you suspect it could all be a clever move on the part of Lego: an extension of the brand that fits perfectly with how a company devoted to the concept of constructivist play wants itself to be seen.

“One of Lego’s strengths is its impermanence,” says Paul Bailey of the London brand consultancy 1977 Design. “It’s being used in things like urban planning because, at its core, Lego is about building and innovation. It was never about making toys that looked exactly like a spaceship.” A partnership with a group like MIT strengthens that image of innovation and creativity, and reconnects the company to its original identity, back in the days before the film franchising and the brand partnerships. “I think what Lego is potentially doing here is reiterate, ‘We are a creative platform.’”

It’s that accessibility that gives Lego a bit of credibility in urban planning. Chin at MIT admits the blocks are most valuable to use in participatory design, rather than for their technical specifications. The CityScope team was just hired to create an interactive Lego model for a new transit system in Boston, designed to show residents and other stakeholders how the new transit will affect their community, such as its impact on commuting time and land value.

Other planners have also used Lego to bring regular people into the planning process. Earlier this year, a workshop in London used the Lego Architecture Studio kits to get participants aged four to 84 to create a city from scratch. “It was a fascinating exercise,” says Finn Williams, who led the event. “Over six hours you could almost see the classic stages of the evolution of a city.” Williams, an instructor at the Royal College of Art’s School of Architecture and a self-confessed “Lego fundamentalist” – he jokes that he took the Lego consultant gig because they paid him in bricks – started his career working for architects such as Rem Koolhaas, but switched to planning because he saw an opportunity to influence not only buildings but neighbourhoods. “I felt like there was something going wrong in the system before architects picked up a commission,” he says. “The wrong questions were being asked in briefs.” Part of the solution to poor planning decisions, he explains, is to involve the people who will be affected. Lego is just one piece of the puzzle – or brick in the wall – but he believes it allows local residents to see first-hand the implications of design decisions. “Not many mediums allow people to engage on level platforms in such an engaging and satisfying way.” He is a fan of Eliasson’s Connectivity Project for that very reason: “Where Lego is most successful in urbanism is when is starts a conversation about the bigger issues of planning.”

In this sense, it doesn’t matter that Lego can’t accurately model cities. The professional “Lego builder” Warren Elsmore, who organised the Brick 2014 Lego conference in London last month and has created everything from St Pancras Station to Amsterdam canal houses, told me the realism of his models relies on the same kinds of tromp l’oeil effects you see in the castles at Disneyland.

Indeed, there is something uncanny about the way Lego can mirror our real cities. At his workshop in London, Williams gave the participants a few rules, a level playing field and then set them loose to create their cities from scratch. Yet a pattern quickly emerged. “There were large, flat Lego baseplates that immediately took up all the space in the city and left no public realm,” Williams says. “We swiftly had to remove all these big plates so people would be forced to think about their building in relation to the other people’s, instead of building as much as they possibly could.” Eventually, the participants began to demolish structures that didn’t fit the emerging cityscape. They had faced the same perils, possibilities and problems in their Lego city as they might if working on a real one.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion